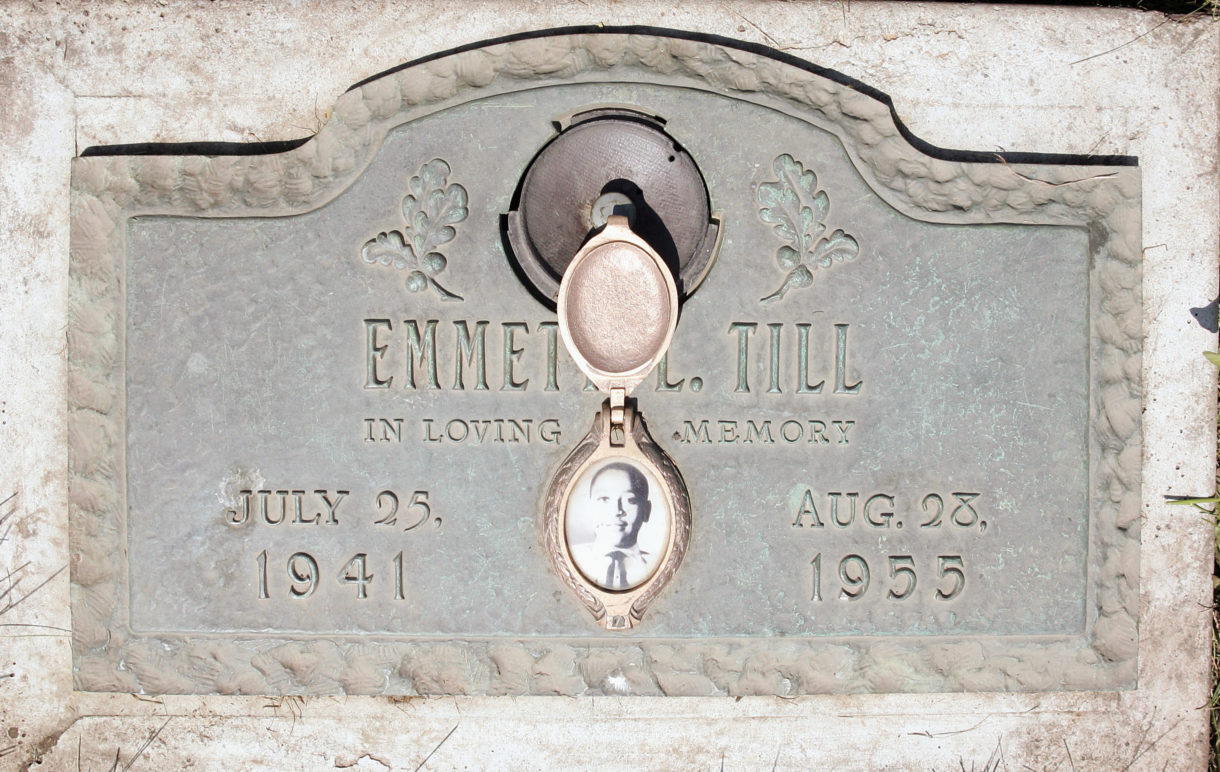

On Aug. 28, 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till was gruesomely lynched in the small town of Money, Miss. He was a boy from Chicago, visiting his relatives. Although the case is now 63 years old, a recent book has spurred the Department of Justice to reopen the investigation into his death.

Duke professor Tim Tyson has written civil rights history books that have brought national acclaim. Blood Done Sign My Name is a searing memoir of a racial killing in his hometown of Oxford, N.C., in 1970. His father, a Methodist minister, sided with the town’s black community and was excoriated as a white traitor.

Tyson’s life and worldview were never the same.

A few weeks after Blood Done Sign My Name‘s publication, Tyson got a phone call. A fan was on the other end raving about how much her mother-in-law loved his memoir and she wanted to meet him.

“You know I sort of pretended she hadn’t said it and was getting off the phone, and then she said, ‘You might know my mother-in-law, her name was Carolyn Bryant?’ ”

Indeed Tyson did. Carolyn Bryant had been at the center of one of the country’s most infamous racial slayings — the killing of Emmett Till in Mississippi in 1955. Tyson arranged to meet her.

“I went to her house I walked in the door. She gave me a big hug. She served me pound cake and coffee. And she seemed like pretty much any kind of Methodist church lady I’ve ever known in my life.”

Tortured and killed

In 1955, Carolyn Bryant was a strikingly beautiful 21-year-old Mississippi woman, who had married into a rough and violent working-class family. She and her husband were the owners of a small rural grocery store. Bryant was behind the counter that late August day in the summer of 1955, when Emmett Till came in to buy some bubble gum. Tyson says what happened next still is a matter of dispute.

“We do know a 14-year-old black boy from Chicago visiting his relatives in Mississippi had some kind of harmless encounter with a white woman,” explained Tyson. “And her kinsmen came in the middle of the night snatched him away from his family at 2:30 in the morning. Drunk men with guns dragged him off, tortured him to death in a tool equipment shed in unspeakable ways and threw his dead body in the river.”

Carolyn Bryant’s husband and brother-in-law were charged with murdering Till. In her statement to her husband’s lawyer at the time, Carolyn said Emmett Till had been sassy and disrespectful when he was at the counter. She told the lawyer that, as the boy left the store, he turned around and said, “Bye baby!”

But Bryant’s story eventually changed. And the change came after Emmett Till was buried back in his hometown of Chicago.

An open casket burial became a national story

Till’s mother, Mamie Till Bradley, held an open casket funeral for her son. Jet Magazine covered it and published a national story along with a gruesome photo of the badly mutilated child lying in repose. The story and the photo horrified and infuriated African-Americans across the country.

The powerful NAACP and Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters took up the cause of Till’s lynching, and the story spread to major news outlets. So when Carolyn Bryant took the stand back in Mississippi to testify in her husband’s murder trial, her story had changed. “She essentially told the age-old story of the black beast rapist,” Tyson says. “It was a well-worn story that Southerners black and white have heard for a long time.”

Bryant testified that Till grabbed her by the hips and spoke of sex with white women. Even the trial judge was skeptical, and although he allowed Bryant to testify, he sent the jury out of the courtroom while she did. The judge appeared to understand that, in 1955 in Mississippi, testimony of dubious provenance wasn’t needed for an all-white jury to find Bryant’s husband and brother-in-law innocent of the charges.

In fact, it took little more than an hour to deliver a verdict of not guilty.

‘That part’s not true’

Nearly 50 years later, in her daughter-in-law’s living room, Tyson says Carolyn Bryant told him that she had lied that day in court.

“She started muttering, ‘Well they’re all dead now anyway.’ ” Of the attack, the sexual assault, she said, “That part’s not true.”

Tyson’s subsequent book, The Blood of Emmett Till, published in 2017, caused a sensation. Not so much because Bryant’s revelation was really all that shocking, but because white Southerners involved in lynching cases usually take the truth of what happened to their graves.

This summer, the FBI quietly reopened the case, requesting the author’s notes and tapes of his interview with Bryant. The Justice Department declined NPR’s request for comment, citing the ongoing investigation.

Carolyn Bryant is now in her 80s and lives with her daughter-in-law Marsha Bryant, in North Carolina. In an interview with NPR, Marsha Bryant denied her mother-in-law had confessed to lying to author Tim Tyson. “What she said on the stand is what’s she said all along. She didn’t change her story,” said Bryant.

This is the second time the Department of Justice has reopened the case. The first was back in 2004. But at that time, a Mississippi grand jury refused to take any further legal action. Nearly 15 years later, Carolyn Bryant is the only person connected to the case who is still alive, and few believe the Justice Department would go so far as to indict her now. Slixy

Jim Coleman is a law professor at Duke University and has followed the case. “I don’t see anything that would be accomplished by a federal reopening of the case,” he said, “other than the publicity of the Justice Department having reopened the case.”

The year after Till was killed, in a Look magazine article, Bryant’s husband and brother-in-law admitted they had killed Till. They said that they had struck a blow for white supremacy and were proud to do it and that the teenager had it coming.

The Emmett Till generation

The case became a shame upon the nation and a Southern disgrace.

It inspired a generation of young black men and women across the country to go to the Deep South, risk their lives and organize African-Americans to vote.

In 1955, activist Charles Cobb was about same age as Emmett Till. “I can remember even now standing on street corner looking at that photograph with my friends of his body,” remembered Cobb. “Those of us who made our way into the civil rights movement in the 1960s call ourselves the Emmett Till generation.”

In 1962, Cobb left Howard University in Washington, D.C., and headed for the Mississippi Delta, where Till was killed. He spent the next five years organizing for SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

“We were an organization of organizers,” he said. “And we embedded ourselves in rural black communities, trying to persuade people that gaining the right to vote was worth putting their lives at risk, putting their jobs at risk, putting their homes at risk.”

The men who killed a beautiful child from Chicago in order to terrorize the local black community believed they had served the cause of white supremacy well. But in fact, they had done anything but.

Though it would take another decade, the seeds of the Voting Rights Act were planted in 1955, in Mississippi, in Emmett Till’s blood.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))