Dr. Pierre Rollin is an expert on Ebola with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Two and a half weeks ago he returned from the Democratic Republic of Congo, which is now in the fourth month of an Ebola outbreak.

It’s not the first time the disease has struck in Congo. Rollin has been visiting for more than 20 years to respond to periodic Ebola outbreaks. And he says there’s a pattern to these eruptions.

“Usually you have one or two months before you detect it,” explains Rollin. By then enough cases start cropping up that one of them reaches a health worker who recognizes that it might be Ebola and orders up a test.

As soon as the case is identified as Ebola, response teams flood into the outbreak zone. They isolate those who are already sick and identify anyone who has had contact with them — and any contacts of those contacts – so they can be monitored and, if necessary, isolated in turn. Within a short time the outbreak is quashed. “Three, four months maximum,” says Rollin.

But that’s how long the current outbreak has been spreading through DRC. And Rollin says by many measures this time around it’s as if they’re stuck at square one.

“It’s as if we’re just starting now when in fact we started three months ago,” says Rollin. “We’re not making any progress.”

More than 300 people have already been infected, making this outbreak the biggest in DRC history. For weeks, the count of new infections has remained stubbornly at around 30 new cases per week.

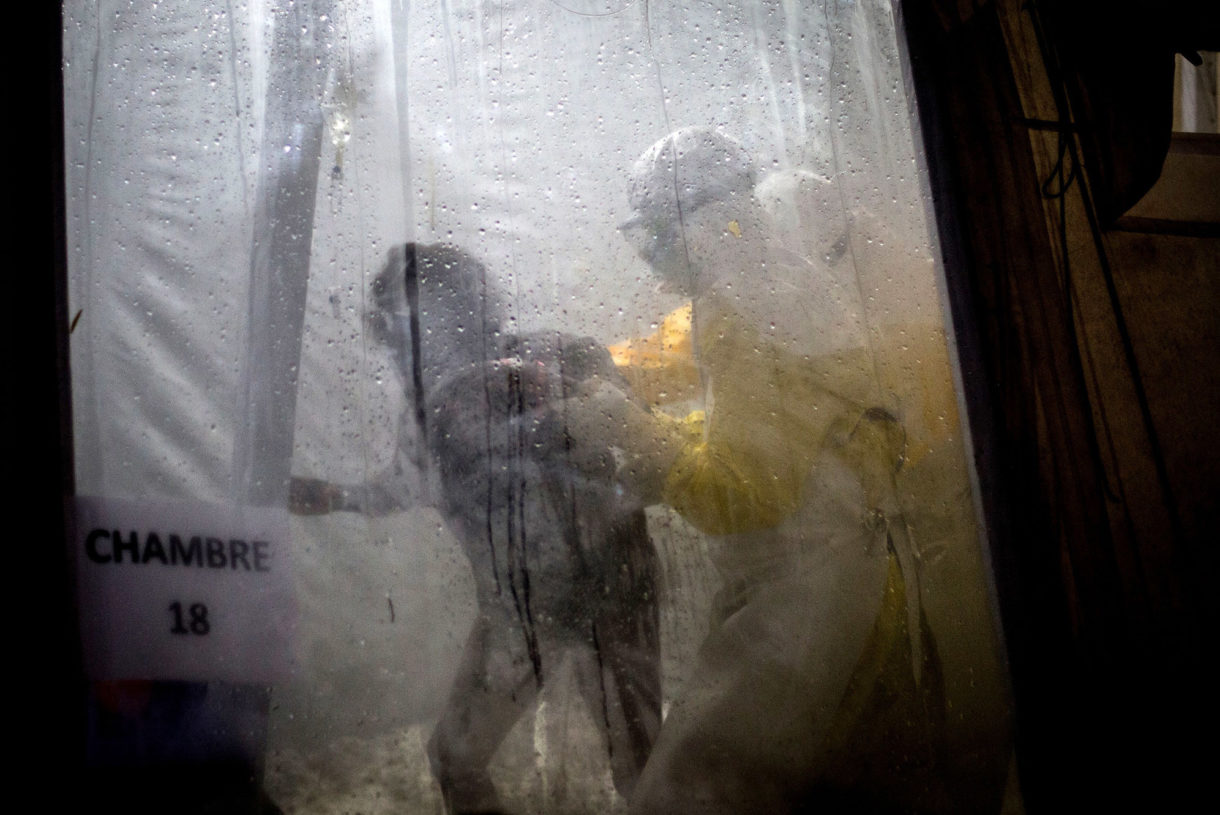

Also, says Rollin, “there are still a lot of people that are not detected in time.” They die in their homes, cared for by relatives who don’t know to use protective gear – setting off new chains of transmission.

Perhaps most alarmingly, says Rollin, “I was looking at the last 30 days of cases and two-thirds of them were of unknown origin – so we can’t trace them.”

The reason for these setbacks is clear: Unlike previous outbreaks in DRC this one is taking place in an eastern part of the country that is wracked by conflict.

Response teams are continually finding themselves blocked by multiple armed rebel groups who launch attacks on the government and civilians. The health workers have also been caught in crossfire between clashing factions within the Congolese military. And the responders have been repeatedly rejected and even assaulted by members of the community who are deeply distrustful of anyone associated with the government — including health workers.

Rollin worries the situation could get even worse in late December, when DRC is set to hold national elections.

“We have no idea what’s going to happen, what the result will be – and whether it’s going to be accepted,” he says.

The fear is the results will be disputed, sparking more violence.

Rollin is not the only one expressing concern. J. Stephen Morrison is the co-author of a recent position paper published by his think tank, laying out some dire possibilities for how things could play out in DRC.

“The terrible scenario is the one in which there are escalated attacks, including targeting of health workers,” says Morrison, who directs the Global Health Policy Center at the Washington D.C.-based Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“That could very rapidly trigger a decision to evacuate,” says Morrison.

He points out that there are currently hundreds of foreign and Congolese health workers in the outbreak zone — including teams that have given more than 30,000 people a new vaccine widely credited as the reason the outbreak hasn’t spiraled out of control.

“You take that away, you’ve removed a dampener,” says Morrison. “You’re going to see a sharp escalation of this outbreak. And your risks of export into the region and beyond go through the ceiling.”

So, he says, you’d think international governments would be crafting an aggressive intervention. “But I see no evidence whatsoever that there’s any mobilization of this kind happening.”

Peter Salama, the World Health Organization’s deputy director-general of Emergency Preparedness and Response, says he shares Morrison’s fears. But he’s also more optimistic.

Salama notes that there’s a longstanding U.N. peacekeeping force in DRC. And Salama, who is normally based in Geneva, met with them last week, as part of a visit to the outbreak zone by WHO’s Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and Jean-Pierre Lacroix, under-secretary-general for the U.N. Peacekeeping Forces.

“We discussed how the force could really act as more than just a reactive force,” says Salama, “but a deterrent to [militant groups] making incursions into Beni,” the city with a population of several hundred thousand that is the current epicenter of the outbreak.

It’s a daunting task, however. On Thursday, the U.N. announced that seven of its peacekeepers were killed and 10 wounded during a joint operation with the Congolese military against a rebel group in the area.

And Salama says even in the best case scenario, ending this outbreak will take at least six more months: The circumstances make this “probably … the most difficult context we’ve ever had to deal with in an Ebola outbreak.”

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))