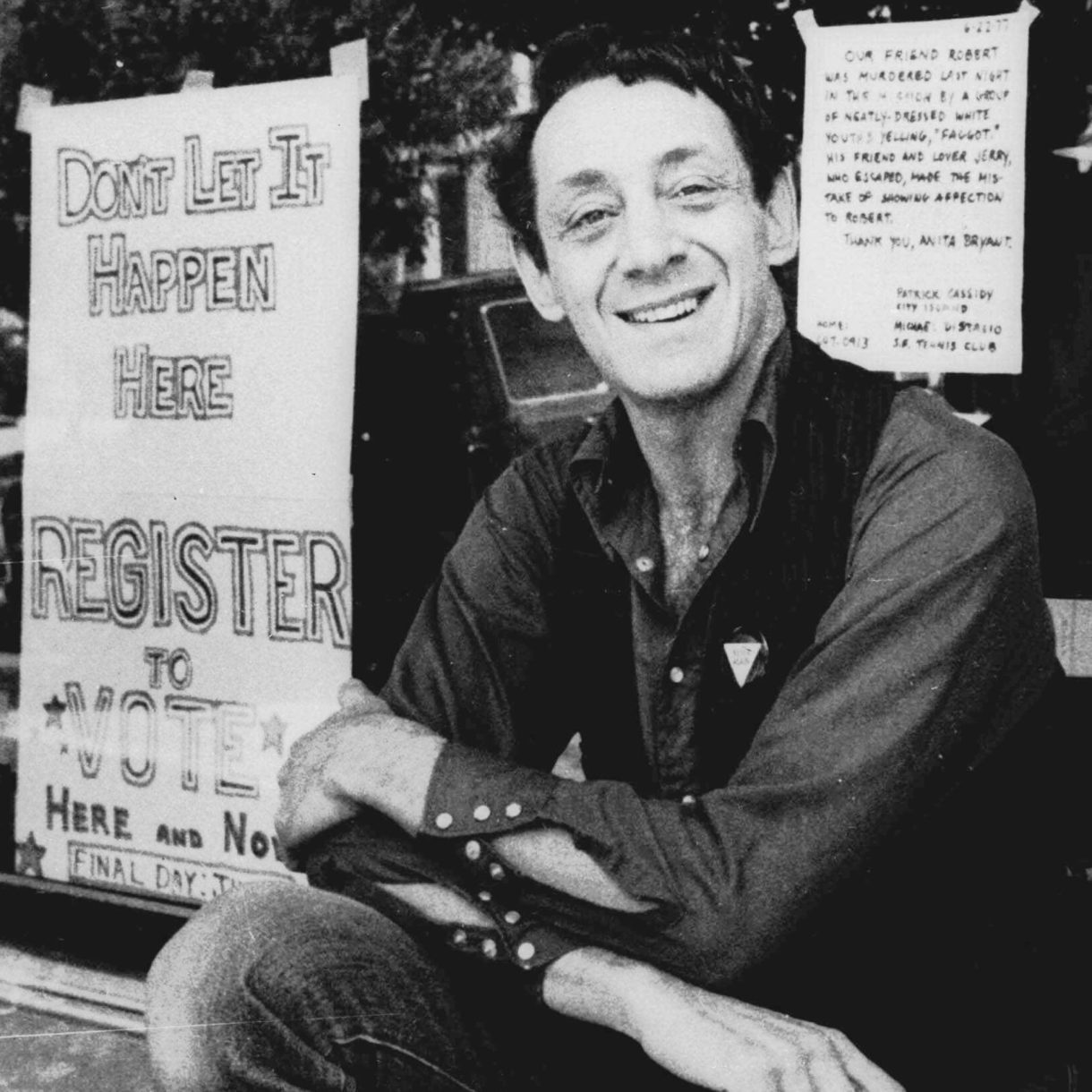

In this month’s midterm elections, Colorado elected the nation’s first openly gay governor. Voters across the country sent a record number of LGBT candidates to Congress. These victories come 40 years after the assassination of the first openly gay elected official in California — Harvey Milk.

Milk was elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1977. In 1978, under his urging, the city council passed a gay rights ordinance that protected gay people from being fired from their jobs. His advocacy angered many.

On Nov. 27, 1978, Supervisor Milk and Mayor George Moscone were assassinated by Dan White, a former police officer and former city supervisor who had clashed with Milk over LGBTQ issues. After shooting the mayor, White entered Milk’s office and shot him five times at his desk.

Milk’s murder transformed national politics

The success of LGBTQ candidates in the midterm elections would have been hard to imagine four decades ago when Milk first won office. In California at that time, a conservative state senator named John Briggs was pushing a statewide ballot measure, Proposition 6, to ban gay and lesbian teachers. Harvey Milk led the fight against the proposition, debating Briggs around the state.

“And if in your statements here and all these newspapers and tonight, that child molestation is not an issue,” argued Milk, “if it is not an issue, why do you put out literature that hammers it home? Why do you play on that myth and fear?”

That November, voters overwhelmingly defeated the Briggs initiative.

But three weeks later, this announcement from the then President of the City’s Board of Supervisors, Dianne Feinstein, shocked the city:

“Both Mayor Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk have been shot and killed. The suspect is Supervisor Dan White.”

It changed the world

Feinstein, now a U.S. senator, remembers the day well. She found the body of her colleague Harvey Milk.

“And it’s still traumatic,” she says. “Because I tried to get a pulse in his wrist and put my finger in a bullet hole. And it was clear he was dead. And that changed the world.”

It also changed the trajectory of the life of Cleve Jones, then a 24-year-old intern for Milk. He thought the murder meant the end of the gay rights movement. That night he organized a candle-lit march from the Castro District up Market Street.

“And we marched to Civic Center and filled it with candlelight,” he recalled. “And I remember standing in that huge crowd and realizing that of course it wasn’t over. It was, in fact, just beginning.”

Jones is now a prominent human rights activist and author. He co-founder the San Francisco AIDS Foundation and founded the AIDS Memorial Quilt project.

Grateful for Milk and others who changed the world

It was a kind of political awakening for many who came of age in the years that followed. Today, the seat Milk held when he was killed is occupied by another openly gay man, Rafael Mandelman.

“As someone who was 5 years old when he was shot,” says Mandelman, “I am continually grateful not just for Harvey but for the folks of that generation who really did change the world.”

But before all that happened, Mandelman says, Milk had already changed himself. The closeted former Wall Street stockbroker left New York and came to San Francisco where he could open a small business and be out. That was the beginning of the change that carries on today, Mandelman continued: “Today young queer professionals certainly can be in San Francisco and be out and proud and work at Salesforce, or you know, in real estate or banks or any aspect of American business and do just fine.”

Mandelman is hoping to build on Milk’s legacy of progressive politics. But he worries that as queer people are priced out of gay neighborhoods like the Castro, it dilutes their political power.

“You know I am the only LGBT person on the Board of Supervisors and that is less representation than our community has had in decades. That’s a little concerning to me.”

But there is much more LGBTQ representation where it would have been hard to imagine four decades ago, from rural Minnesota to Kansas and Arizona. LGBTQ activist Gwenn Craig, who came to San Francisco in the 1970s and worked with Harvey Milk before he was killed, traces it all back to Milk pushing people to come out of the closet.

“I do think that he sort of started this path that made it possible for the openly gay officials that were elected in this last round,” says Craig. “And it makes me so proud.”

And surely would have made Harvey Milk proud, too.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))