Every year, the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation hosts a weekend to celebrate the scholarship students they fund. For the four years that Harold Levy led the foundation, you’d often find him at that event, sitting on the floor, deep in conversation with students.

“Where I come from — a traditional, conservative background — you don’t really see people of authority sitting down on the floor, talking to students one on one,” remembers Alessandro Bailetti, now a Ph.D. a student at New York University School of Medicine. Bailetti, who emigrated from Peru, received a full scholarship from the foundation when he transferred from community college to Levy’s alma mater, Cornell University.

“Harold wanted to know us, he wanted to hear us. He wanted to be on the same level as the scholars and listen to what they needed.”

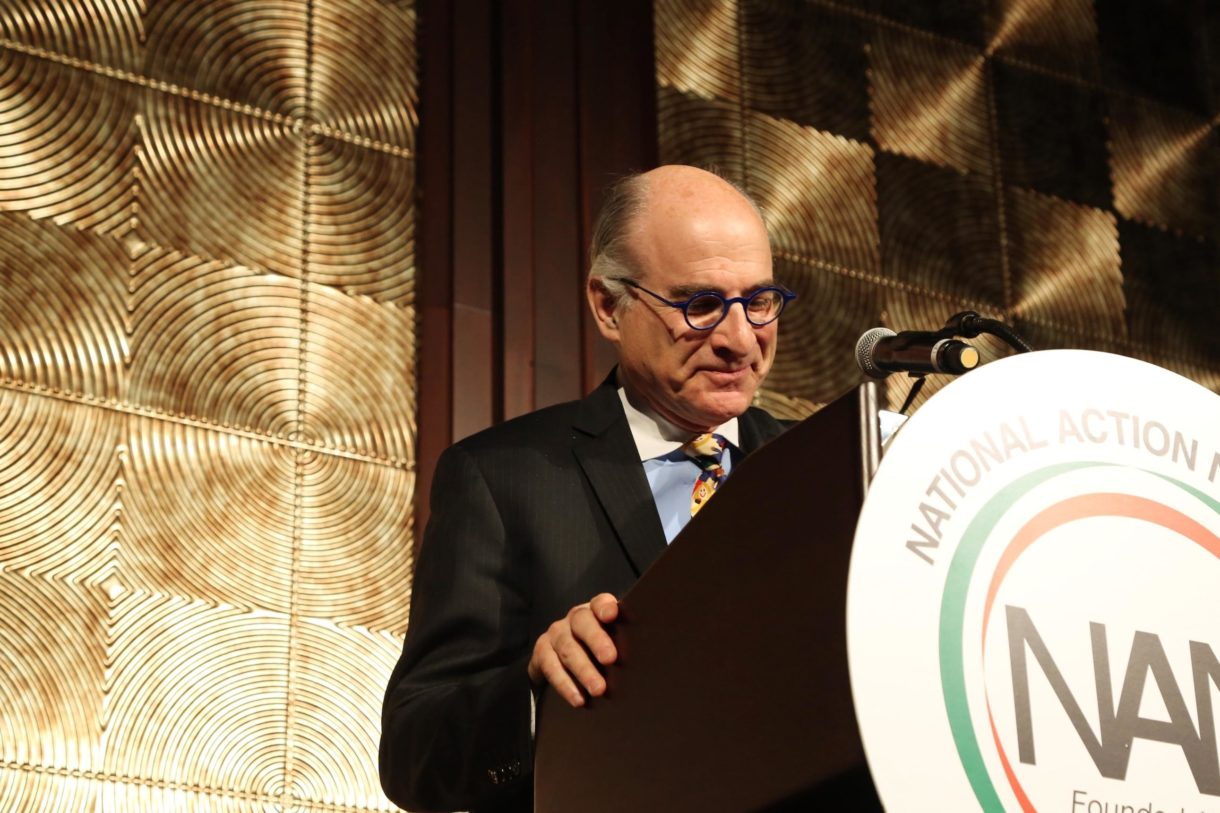

It was a curiosity that came to define Harold Levy, who died Tuesday from ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Levy, who was 65, is perhaps best known as the former head of New York City’s public schools, the nation’s largest public school system.

He arrived at the job from Citigroup and brought with him a unique perspective, albeit a lack of classroom experience. “My job is to be orchestra leader of this great, monstrous enterprise and make sure it sings,” he told a reporter for Education Week in 2000.

During his time as New York City chancellor from 2000 to 2002, Levy had a hand in many layers of the massive system: He created the largest summer school program in the country, established the New York City Teaching Fellows (modeled after Teach for America) and opened up specialized high schools, increasing options for minority students. On Friday, New York City lowered its flags to half-mast to honor his death.

In his later years, he took the helm of the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation (a financial supporter of NPR), which awards some of the largest single scholarships in the country to low-income, high-achieving students. He was a strong advocate for making higher education a more open and diverse place — especially for poor students.

Earlier this year, in an op-ed published in The New York Times, he wrote:

“Too many academically talented children who come from families where household income hovers at the American median of $59,000 or below are shut out of college or shunted away from selective universities. … Comprehensive reforms must come quickly and they must be more visible.”

He urged wealthy donors to “please stop giving to your alma mater,” and if that impulse couldn’t be squashed, to “try earmarking your donation for financial aid for low-income, community college students who have applied to transfer to your alma mater.”

In 2016, Levy addressed a new batch of scholarship recipients with the idea that demography is not destiny. “That was such a profound message to hear,” remembers An Garagiola-Bernier, one of those recipients. Her father had just passed away, and when she met Levy that day, he offered his condolences. “The fact that he knew who I was, or any part of my life, left me awestruck and crying,” she says.

Garagiola-Bernier transferred from a community college to Hamline University, a small private school in Minnesota, thanks to funding from the foundation. Now a junior, she says Levy sent emails congratulating her on her accomplishments and checking in on her schooling. “I was so touched by how he made sure to keep up with my progress.”

Garagiola-Bernier is a first-generation, low-income, Native American student and parent — the type of student that higher education isn’t really used to, she says. But Levy looked beyond all those identifiers. “Harold believed in me when I didn’t believe in myself.”

When his ALS took away his ability to speak, Levy wrote an email to the foundation’s scholarship recipients and alumni, asking them to help keep his message of equity alive.

When Garagiola-Bernier thinks about who will carry on his legacy, she says, “I guess it’s us.”

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))