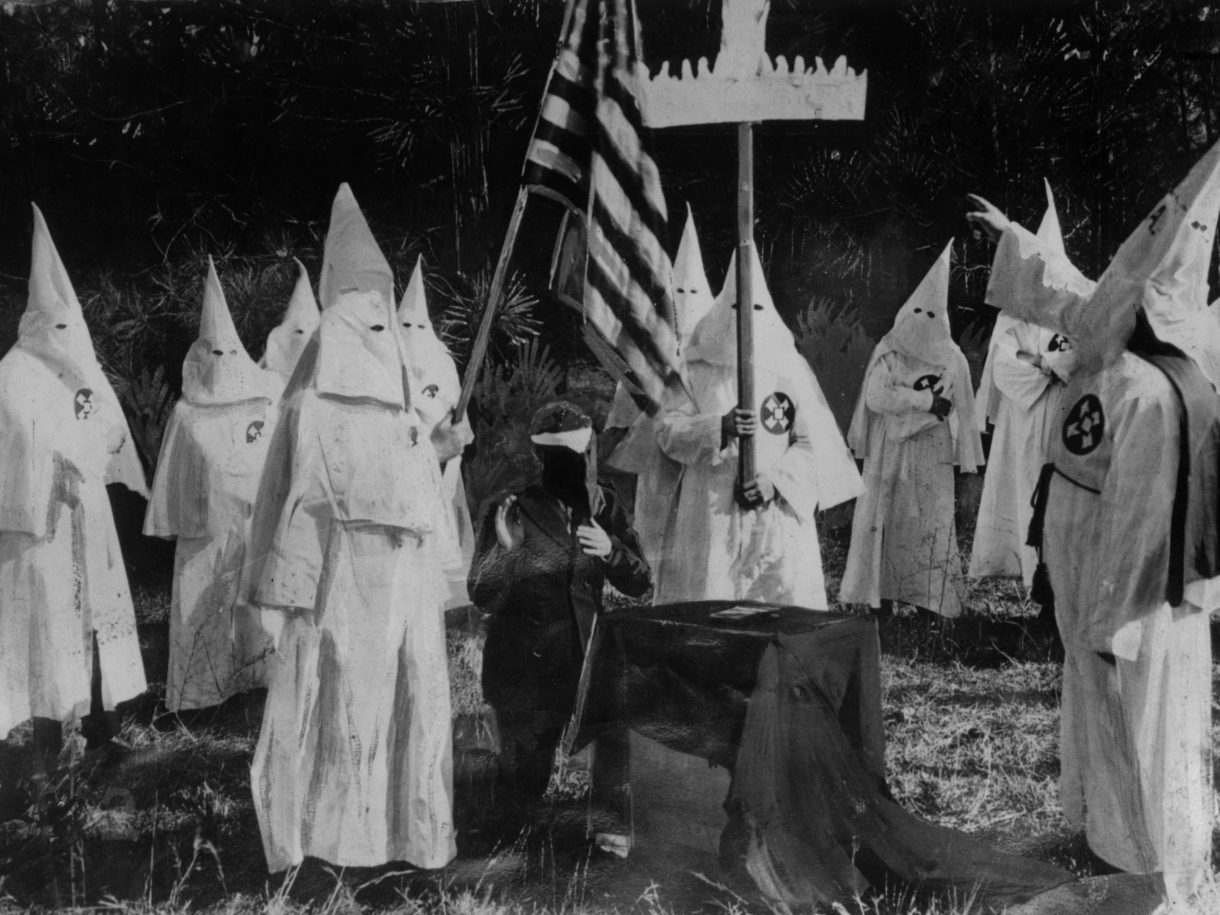

As long as the United States has existed, there’s been some version of white supremacy. But over the centuries, the way white supremacy manifests has changed with the times. This includes multiple iterations of the infamous Ku Klux Klan.

According to the sociologist Kathleen Blee, the Klan first surfaced in large numbers in the 1860s in the aftermath of the Civil War, then again in the 1920s, and yet again during the civil rights era.

Blee is a professor and dean at the University of Pittsburgh, and the author of Inside Organized Racism: Women in the Hate Movement, as well as Understanding Racist Activism: Theory, Methods and Research. She says the anonymity allowed by the internet makes it difficult to track just how much white supremacist activity we’re seeing today.

But despite this difficulty, she and other experts say there’s been an indisputable uptick in hate crimes — and an overall rise in white supremacist violence: Earlier this fall, a gunman shot and killed 11 worshipers at a Pittsburgh synagogue. In 2017, a clash with protesters at the Unite The Right rally in Charlottesville, Va., left one woman dead. In 2015, the shooting at the Mother Emanuel AME church in Charleston, S.C., killed nine black churchgoers. And in 2012, a rampage at the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin in Oak Creek, Wisc., killed six people.

As we consider this spate of racist attacks, we thought it’d be helpful to talk to Blee about the ebbs and flows of white supremacy in the United States — and what, exactly, those past waves say about today’s political climate.

Our conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

First, can we talk about the various phases of white supremacy in the U.S. throughout history — and what caused those ebbs and flows?

The 20th to 21st century Klan actually formed after the Civil War, during the Reconstruction period. Then it was entirely contained within the South, mostly in the rural South. It [was] all men. There were violent attacks on people who were engaged, or [wanted] to be engaged, in the Reconstruction state, [including] freed blacks, southern reconstructionists, politicians and northerners who move to the South. That collapses for a variety of reasons in the 1870s.

Then, the Klan is reborn in the teens, but becomes really big in the early 1920s. And that is the second Klan. That is probably the biggest organized outburst of white supremacy in American history, encompassing millions of members or more. … And that’s not in the South, [it’s] primarily in the North. It’s not marginal. It runs people for office. It has a middle class base. They have an electoral campaign. They are very active in the communities. And they have women’s Klans, who are very active and very effective in some of the communities. That dissolves into mostly scandals around the late ’20s.

Then there’s some fascist activity around the wars — pro-German, some Nazi activity in the United States — not sizable, but obviously extremely troubling.

The Klan and white supremacy reemerge in a bigger and more organized way around the desegregation and civil rights movement — again, mostly in the South, and back to that Southern model: vicious, violent, defensive, Jim Crow and white rights in the South.

And then it kind of ebbs. After a while, it kind of comes back again in the late ’80s and the early 21st Century as another era. And then there’s kind of a network of white supremacism that encompasses the Klan, which is more peripheral by this time. Also Neo-Nazi influence is coming as white power skinheads, racist music, and also neo-Nazi groups. The Klans tend to be super nationalist, but these neo-Nazi groups have a big international agenda.

Then the last wave is where we are now, which is the Internet appears. The movement has been in every other era as movement of people in physical space like in meetings, rallies, protests and demonstrations and so forth. It becomes primarily a virtual world, and as you can see, has its own consequences — many consequences. It’s much harder to track. And then there are these blurred lines between all these various groups that get jumbled together as the alt-right and people who come from the more traditional neo-Nazi world. We’re in a very different world now.

That’s a long history. You mentioned that, for a variety of reasons, the Klan in the Reconstruction era collapsed. What are some of the factors that contributed to that?

I would say two things that mostly contributed to that ebb over time.

One is the white supremacist world, writ large, is very prone to very serious infighting. Internal schisms are quite profound in collapsing white supremacists, even as an entire movement, over time.

What’s that infighting look like? How racist to be?

No, no. It’s almost always power and money. So, for example, the ’20s Klan — I say “Klan” but in every era there were multiple Klans, they all have different names, they all have different leaders — they are trying to extract money from their groups, and they are all fighting about money …. and then over power, and who controls the power, because white supremacy groups don’t elect their leaders right away. To be a leader just means to grab power and control. So there’s a lot of contention in these groups of control.

It’s not ideas. Ideas aren’t that central. They have these certain key ideas that they promulgated — race and anti-Semitic ideas — but the fine points of ideological discussion don’t really occur that much in white supremacist groups, nor do they get people that agitated. It’s not like in other kinds of groups, where people might have various versions of ideas, versions of ideologies. [The Klan] just have kind of core beliefs. But they do tend to fight over ideas for money, power and access to the media.

So that’s the fighting. The other thing is, in different waves of history, there are prosecutions, either by the police or civil prosecutions that collapse groups and movements. Sometimes, there’s kind of a blind eye to white supremacist organizing, but at other times there is really successful either civil or state prosecutions of these groups that do debilitate them.

How does the longevity of white supremacy or these [hate] groups coincide with who has political power?

It’s very hard to create a generalization here. Certain groups, like the Klan, tend to rise and fall based on the threats to who is in power. The 1870s Klan [was] based on the Southern racial state formed during slavery being threatened by Reconstruction. In the 1920s, the idea was that political power [was] being threatened by this wave of immigrants. The 1920s Klan [was] very anti-Catholic, as well as racist and anti-Semitic. Part of this anti-Catholicism [was] based on the idea that Catholics were going to start controlling politics as well as the police.

There’s some really good analysis by some sociologists that showed that the Klan appeared in counties where there was the least racist enforcement of the law. Because in counties where the sheriff and the county government was enforcing racist laws, there was no need for the Klan.

How does this apply to this more recent wave of white supremacy?

Right now, we have an extremely heterogeneous group that we might call white supremacists. So some of them, probably the smallest group, are nationalistic. And probably the larger group are not particularly nationalistic. This is why it’s hard to make generalizations. It’s not the case that nationalist fervor just finds itself in the white supremacist movement. The person accused of the shooting in Pittsburgh is an example. If you look at [his] writings, they’re not nationalistic, they’re in fact anti-nationalistic. And that’s pretty common with white supremacy today — some of them have this sense that their mission is this pan-Aryan mission. They’re fighting global threats to whites and creating a white international defense. So that’s not a nationalist project, that’s an internationalist project.

And the other reason is there’s this idea among white supremacists in the United States that the national government is ZOG — Zionist Occupation Government — and that’s a shorthand way of saying that the national government is secretly controlled by an invisible Jewish cabal. So some of them will be amenable to very local government … they’ll embrace, and work with, and even try to seize control of the government at the county level. But generally, national politics are quite anametha for those two general reasons.

In the 1920s, synagogues were targeted by the KKK. Can you run through other examples of violence like this?

People will say the ’20s Klan was not as violent as other Klans. But that’s really because its violence took a different form. So there, the threat that the Klan manufactured was the threat of being swapped — all the positions of society being taken by the others — so immigrants, Catholics, Jews and so forth. So the violence was things like, for example, I studied deeply the state of Indiana where the Klan was very strong — pushing Catholics school teachers out of their jobs in public schools and getting them fired, running Jewish merchants out of town, creating boycott campaigns, whispering campaigns about somebody’s business that would cause it to collapse. So it’s a different kind of violence but it’s really targeted as expelling from the communities those who are different than the white, native-born Protestants who were the members of the Klan. So it takes different forms in different times. It’s not always the violence that we think about now, like shootings.

When did we start seeing the violence that we see today?

Well, the violence that we see today is not that dissimilar from the violence of the Klan in the ’50s and ’60s, where there was, kind of, the violence of terrorism. So there’s two kinds of violence in white supremacy. There’s the “go out and beat up people on the street” violence — that’s kind of the skinhead violence. And then there’s the sort of strategic violence. You know, the violence that’s really meant to send a message to a big audience, so that the message is dispersed and the victims are way beyond the people who are actually injured.

You see that in the ’50s, ’60s in the South, and you see it now.

I was wondering if we could kind of talk a little bit about the language we use when we talk about mass killings that are related to race, religion or ethnicity — especially about the second type of violence, “strategic violence,” that you describe. I’ve seen people use the phrase “domestic terrorism.” What do you make of that phrase?

Terrorism means violence that’s committed to further a political or ideological or social goal. By that definition, almost all white supremacist violence is domestic terrorism, because it’s trying to send a message, right? Then there’s that political issue about what should be legally considered domestic terrorism, and what should be considered terrorism. And that’s just an argument of politics, that’s not really an argument about definitions right now.

How these things get coded by states and federal governments is quite variable depending on who’s defining categories. But from the researcher point of view, these are terrorist acts because they are meant to send a message. That is the definition of terrorism. So it’s not just, you don’t bomb a synagogue or shoot people in a black church just because you’re trying to send a message to those victims or even to those victims and their immediate family. It’s meant to be a much broader message, and really that’s the definition of terrorism.

I think what we don’t want is for all acts of white supremacist violence to be thought of as just the product of somebody who has a troubled psyche. Because that just leaves out the whole picture of why they focus on certain social groups for one thing. [And] why they take this kind of mass horrific feature … so I think to really understand the tie between white supremacism and the acts of violence that come out of white supremacism, it’s important to think about that bigger message that was intended to be sent.

What are the most effective strategies to combat these ideas of white supremacy, or this violence?

I’d say the most effective strategy is to educate people about it, because it really thrives on being hidden and appearing to be something other than it is. I mean, millions of white supremacist groups have often targeted young people, and they do so often in a way that’s not clear to the young person that these are white supremacists, they appear to be just your friends and your new social life, like people on the edges who seem exciting. … And so helping people understand how white supremacists operate in high schools, and the military, and all kinds of sectors of society gives people the resources the understanding to not be pulled into those kinds of worlds.

Twenty years, or even 10 years ago, I would have said it’s really effective to sue these groups and bring them down financially, which was what the Southern Poverty Law Center was doing.

[Now,] they don’t have property; they operate in a virtual space. So the strategies of combating racial extremism have to change with the changing nature of it.9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))