If all the world goes to hell, don’t say Jerry Brown didn’t try to warn you.

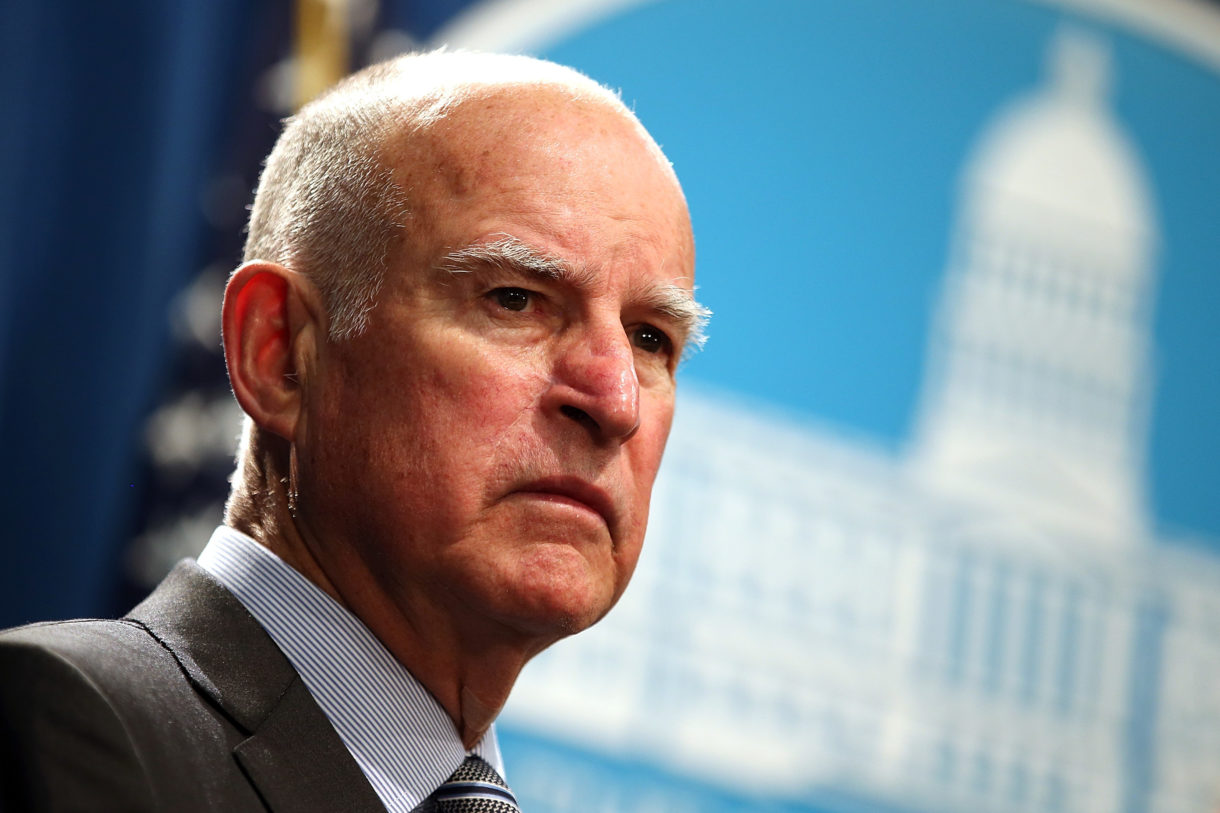

“The climate [change] threat is real. It’s a clear and present danger,” the unconventional and legendary Democrat who will soon term out as California governor told NPR’s Ari Shapiro Tuesday in an interview airing on All Things Considered. “And it’s going to get here much sooner” than many people realize.

“It’s damn dangerous,” Brown said of a possible nuclear war destroying much of the world in mere moments. “And I would say most politicians are 100 percent asleep with respect to this particular issue.”

He also discussed a booming economy that has nevertheless left many working Americans (and Californians) behind: “The engine of capitalism, which is so powerful — it has its negative, dark side as well as its bright and shiny side.”

Brown spoke about climate change, nuclear proliferation, capitalism and more in the wide-ranging interview, as he sat in the breakfast nook Tuesday morning at the governor’s mansion he renovated in downtown Sacramento. His two dogs, Colusa Brown and Cali Brown, frolicked alongside him.

He spoke in the waning days of a political career that has spanned more than 50 years, a record four terms as California governor — from 1975-1983 and since 2011 — and three unsuccessful runs for president, in 1976, 1980 and 1990. Democratic Gov.-elect Gavin Newsom will take over the world’s fifth-largest economy early next year.

In his final years as governor, and particularly after Donald Trump’s election as president, Brown sought to position himself as a worldwide leader on climate change. He has traveled to the Vatican, met with Chinese President Xi Jinping, and taken on a formal role with the United Nations. The man once mocked as “Governor Moonbeam” during his first stint leading California even hosted his own Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco this fall that culminated in an announcement that the state will launch its own satellite to help track and reduce climate pollutants.

Brown worries, however, that the momentum from the Paris climate accord has waned and describes this month’s United Nations follow-up climate conference in Poland as “abysmal.”

At home, the governor has presided over some of California’s largest and most destructive wildfires in history, including the Camp Fire that he and Newsom toured with President Trump last month.

Brown argues that the world, and in particular the Trump administration, aren’t doing nearly enough to fight climate change.

“I’m sure that the political leaders will respond after we have four or five more disastrous fires and four or five more floods and hurricanes and tornadoes and all that,” Brown said in Tuesday’s interview.

“The problem is, the cost will be much higher and the political wreckage that much greater — because the burden of spending to recoup, to adapt and to transition to a noncarbon world will be much higher, much harder, and will be wrenching to the democratic political system,” he says.

The governor also sees great danger in nuclear weapons falling into the wrong hands. Earlier this year, Brown joined the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists — the group known for its Doomsday Clock — as executive chairman.

“There’s still a major threat — from terrorism, from other countries, from blunder,” he says. “And people are almost totally asleep to that ever present danger. And within a matter of hours, human civilization could be extinguished. That’s real.”

Closer to home, Brown is concerned about the effects on his state of unbridled capitalism, a system he calls a “productive” but “not perfect.”

“Capitalism responds to incentives, to human desire, to restlessness, and even to put it more bluntly, greed,” he says. “And that drives it forward. But it drives forward in a way that always overshoots its mark” and leads to recessions.

And as the economy evolves, with real estate prices shooting up and automation overwhelming the labor market, “a lot of people are now what they call redundant — or put more harshly, surplus — because the economy doesn’t have a role for them. And that’s where creative political leaders are going to have to find a way to tame capitalism, restructure it,” he says.

In many ways, California has offered among the most stark examples of capitalism’s pros and cons during Brown’s final stint as governor.

When he returned to the state Capitol in 2011, California was still climbing out of the Great Recession and faced a $27 billion deficit. Brown spent much of his first two years persuading the Democrats who controlled the state Legislature to join him in making steep budget cuts.

“That took fortitude against the tendency of the Democratic Party to spend on almost anything that somebody comes up with that satisfies one of the key constituencies,” he says.

The governor then campaigned hard for a ballot measure to raise the state’s sales and income taxes. Proposition 30’s passage in November 2012 proved a turning point in his governorship — both for the state and for Brown himself. Along with the previous spending cuts and economic recovery, the additional tax revenue has turned that $27 billion deficit into what is now a large surplus.

That gave him the financial and political capital for much of the rest of his agenda. He won nearly every major battle he chose to fight at the state Capitol: an extension of California’s cap-and-trade system to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions, a gas tax and vehicle fee increase to fund transportation projects, and overhauls of the state’s school funding and criminal justice systems.

Yet on Brown’s watch, California has become a much more expensive place to live. For millions of people, it’s simply unaffordable. The state doesn’t just face a housing crisis; many of its cities face homelessness crises. That, in turn, has led to a poverty crisis.

The governor chose not to seek an overhaul of the myriad state and local laws and regulations that raise the cost and lengthen the construction timeline of housing developments.

“We’ve done quite a lot for what the state can do,” he says. “But there’s a lot of resistance to changes, to density in neighborhoods that don’t want density.”

As for the state’s high poverty rate, Brown points to several actions he took — many pushed by legislative Democrats — including a minimum wage increase, a state earned income tax credit for low-income workers, and an expansion of California’s Medicaid program under the Affordable Care Act.

He has also spent a great deal of time and energy on reshaping California’s criminal justice system — including the reversal of a tough-on-crime trend that he helped jump-start during his first stint as governor.

Brown signed legislation that shifted the responsibility for low-level offenders from the state to counties and campaigned for a 2016 ballot measure that made it easier for state inmates to be released from prison if they demonstrate good behavior.

Brown notes that the state has nearly tripled its number of prisons from 12 to 35 over the past two decades while its prison population rose from 25,000 to 173,000.

“How long do you want to lock somebody up?” he asks. “At what expense? And I would say we’ve gone way overboard and we have to very carefully pull back.”

That Brown has accomplished nearly every goal he set out for himself during his second stint as governor is due not just to his own popularity but also to his fellow Democrats’ lock on power in a deep blue state.

But he sees himself as a centrist. And although he scorns California Republicans as “irrelevant” for their embrace of Trump, he fears the state may shift too far to the left after he leaves office.

“The weakness of the Republican Party has let the Democratic Party, I think, go get further out than I think the majority of people want,” Brown says. “So there’s plenty of opportunity for Republicans if they just pause, look at the world as it really is, and try to come up with something in the tradition of Lincoln and Eisenhower and other great Republicans.”

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))