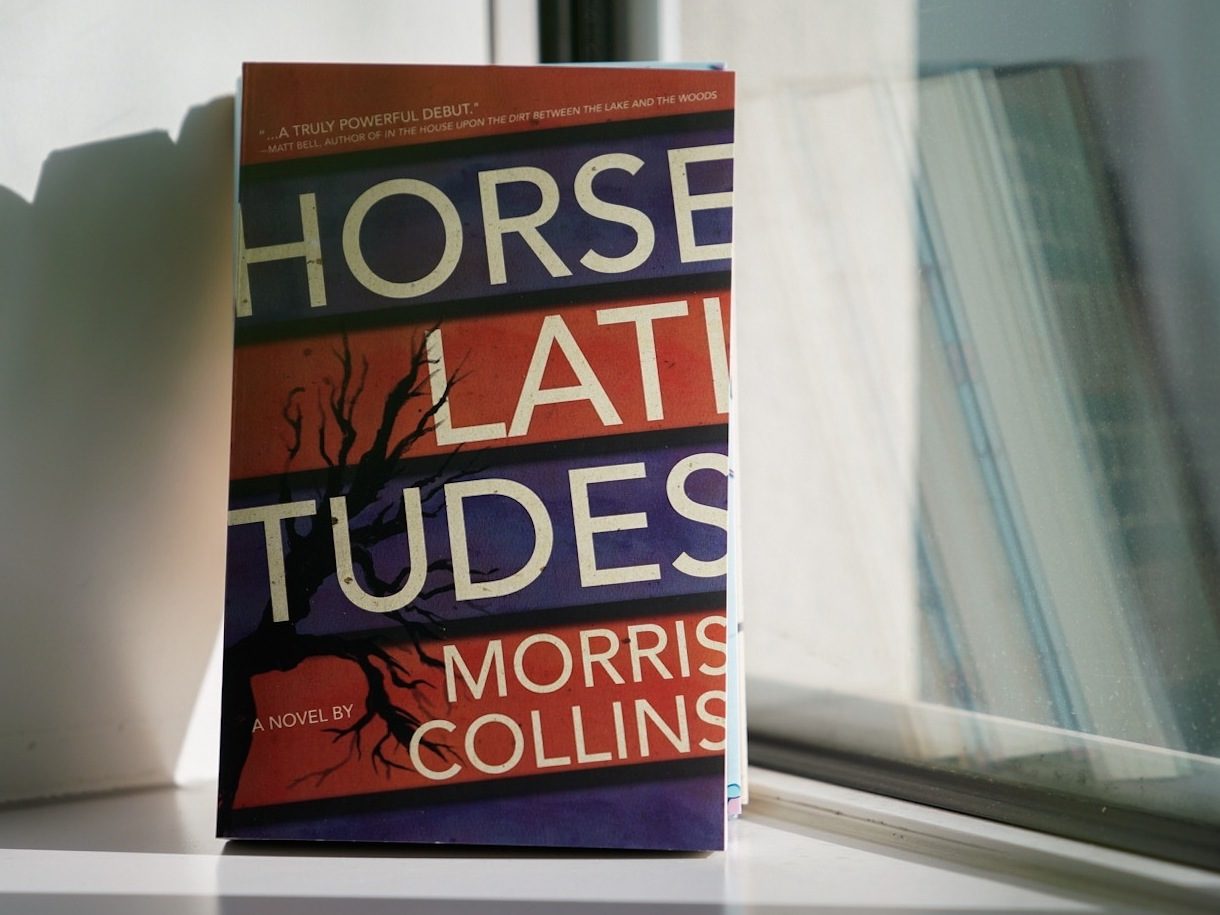

Morris Collins’ Horse Latitudes is one of the most impressive debuts I’ve read. A hybrid narrative that’s part thriller, part surreal noir, and part tropical gothic, it reads like a collaboration between William Faulkner, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, and Hunter S. Thompson, as directed by David Lynch.

Ethan is a New York photographer whose crumbling marriage ends when his wife commits herself to a mental institution after being raped by a stranger. Confused and haunted by guilt over not being able to help her, Ethan flees to Mexico. He doesn’t know if he wants to find himself, find some sense of purpose, or just drink himself into oblivion and find death at the hands of a machete-wielding gangbanger. While figuring it out, he gets in a bar fight, smashes a bottle into the face of a man with cartel connections, and ends up on a journey to the interior of the country to save a young woman from being trafficked — a journey that will put him in touch with violent gangs, crazy expatriates, strange detectives, mystics, and the ubiquitous aftermath of colonialism.

The beauty of Horse Latitudes comes from its combination of elements. It’s firmly rooted in literary fiction, but branches out into pulpy adventure and thrillers — and it hides a scathing political critique under the surface. Collins is aware of his identity as a white American author, and uses it to attack the idea of the white savior, presenting Americans as lost, lustful gringos who come to drink and have sex on the corrupt and rotting ruins left by U.S. intervention in Central America. At one point, Ethan confronts himself about it:

What are you, he thought, a f—— conquistador? The great white hope come to save the natives from themselves? You pitiful drunk a——. Too bad for you, the Third World isn’t all Club Med and mangoes. Too bad the Chiquita Banana Girl happens to be mad.

There is something special in this book that I wasn’t expecting, and that doesn’t jump out at you immediately: surrealism. As the narrative builds, things get progressively weirder. It starts with a singing, crying dwarf who could have been pulled from a Tom Waits song. Then a slew of things come at you: Multicolored lizards everywhere. Strange sounds. Bizarre conversations. Eventually, even Ethan notices; he starts feeling like he’s living “on the edge of a dream,” hearing what he calls “carousel music from a different world.” Also, the entire narrative is framed as photo. Ethan is present in every moment — but also thinks about capturing it, and analyzes the lighting regardless of the situation.

The writing in Horse Latitudes is superb. Collins has a knack for witty dialogue and vivid descriptions of shantytowns, coastal towns, guerilla violence, and roadside poverty. Unfortunately, the beautiful prose that makes most of the novel so enjoyable gets in the way towards the end. Even during a boat chase along a river, plagued with sickness and mosquitos and evil men close behind, Collins spends two paragraphs describing the colors in the sky and how the sun “rose quickly — it crested the far gray horizon and then it was overhead — with the sea opening in layers of aqueous shades to its light: aqua to periwinkle to azure, all lined, intermittently, with the purple shadow of risen reefs where the sea caught and foamed.” The worst part about this is that, in other places, Collins shows he can do the opposite very well: “The raft rocked. The scraping pole. The waiting lights. The jungle.”

Even so, Horse Latitudes is gripping and wildly entertaining. It takes readers on a tour of Central America that shows the destruction and political turmoil caused by US intervention, while offering a fairy-tale-like story about a lost man trying to run away from the ghost of a failed relationship that ended horribly. Most importantly, this book makes a bold statement: Morris Collins is an author to watch.

Gabino Iglesias is an author, book reviewer and professor living in Austin, Texas. Find him on Twitter at @Gabino_Iglesias.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))