Around three-quarters of a century after the Holocaust ended with the extermination of six million Jews, some survivors, as well as victims’ families and estates, are receiving reparations from France, in acknowledgment of the government’s role in deporting them to Nazi death camps via French trains.

Forty-nine people who made it out of the Holocaust alive are receiving around $400,000 each, according to former Ambassador Stuart Eizenstat, the State Department’s expert adviser on Holocaust-era issues, who helped negotiate the agreement. He said 32 spouses of deportees who died will get up to $100,000, depending on how long their spouse lived. Heirs and estates of deportees or their spouses are also getting paid.

The money is the second and last round of payments from $60 million France provided following a 2014 agreement in exchange for recipients relinquishing the right to sue.

The State Department’s Holocaust Deportation Claims Program was charged with processing applications and divvying up the funds specifically for non-French victims deported from France via the state-owned railway system S.N.C.F. That group had been ineligible for compensation under prior agreements and settlements.

“These people were largely ignored,” Eizenstat said.

Leo Bretholz, who in 1942 escaped from an Auschwitz-bound French train, helped change that. After relocating to Maryland, he fought to prevent the S.N.C.F. from bidding on a local rail system and also urged France to pay reparations.

The Vienna-born man died in 2014 at the age of 93. But Eizenstat said his heirs are receiving around $400,000 under the agreement.

In all, Eizenstat said around 900 people have been approved.

“It’s about justice and recognition and feeling acknowledgement,” Greg Schneider, executive vice president of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany told NPR.

And for some, the funds also provide a financial lifeline.

Studies show many Holocaust survivors live at or beneath the poverty line for reasons that are manifold.

“There is no inherited wealth,” Schneider said of survivors whose family assets may have been stolen in the Holocaust. “They may have been denied education opportunities. When others were in high school, they were in Auschwitz, so they weren’t able to build careers.”

Elderly survivors also may not be able to rely on family — wiped out in the Holocaust — to provide support as they become infirm.

“They feel like it is transformative,” Eizenstat said of recipients, “so in their dwindling years, as they need medical care this can provide it.”

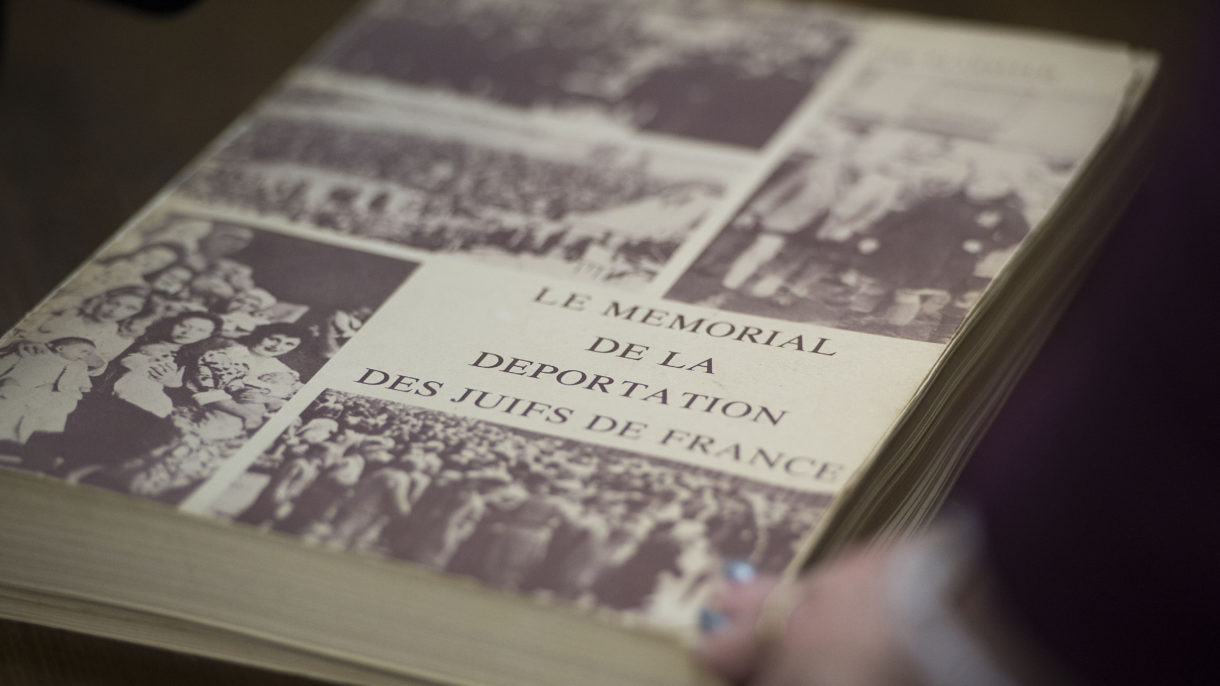

The agreement also highlights the role France and the Vichy government played abetting the attempted extermination of the Jews. “The railways, owned by the government, were complicit in the machinery of murder,” Schneider said.

In 2011, France’s national railway system S.N.C.F. formally apologized for sending thousands of Jews to concentration camps.

Millions of non-Jews were also targeted in the Holocaust, with resisters, homosexuals and the disabled among those killed. Non-Jews are also receiving the payouts.

Several Canadian airmen shot down in battle over France were taken by the Vichy government or Nazis and deported “and we were able to pay them or their relatives,” Eizenstat said.

Still, others may be disappointed.

“There were 867 claims and we approved 386,” Eizenstat said. Some were denied because the claimants were French nationals or citizens, ineligible under this agreement. Others were too distantly related to Holocaust victims.

The money is the final amount to be paid under the agreement; roughly half had already been paid to survivors and families in 2016.

“The page is closed on this chapter,” Eizenstat said.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))