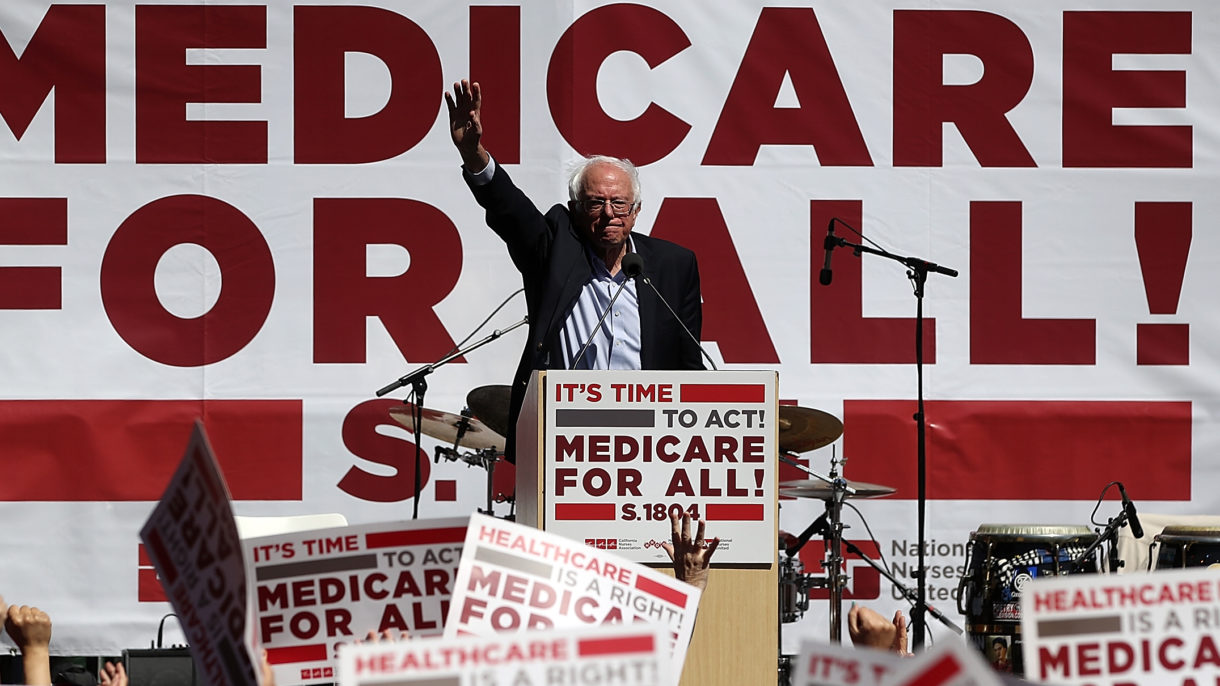

Bernie Sanders is back, but one of his signature policies never left.

In 2015, he introduced Medicare-for-all to many Democrats for the first time. Since Sanders’ first run for president, that type of single-payer health care system has become a mainstream Democratic proposal.

Last week, Sanders launched his second presidential campaign, amid a field of presidential candidates who are trying to figure out how to position themselves around the policy. Trying to stand out from the pack, though — especially on health care — poses a problem: Differentiating yourself means getting into the details, and getting into the details can turn voters off.

Over the last few weeks, candidates have been working to show voters the daylight between their respective health care proposals.

New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker has stressed that he supports Medicare-for-all, and that he wants private insurers to have a role in that system. “Even countries that have vast access to publicly offered health care still have private health care,” he told reporters this month.

Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar says she wants a public option, in the form of letting people buy into Medicaid. As for single-payer health care, she says it’s a possibility in the long-term.

Ohio Sen. Sherrod Brown, who says he’s still debating a run, also wants a sort of public option, but only for people above age 50, whom he would allow to buy in to Medicare. “I think Medicare-for-all will take a while, and it’s difficult,” he told CNN’s State of the Union.

Long story short: In a huge Democratic presidential field, health care is the first issue where candidates are really differentiating themselves.

Bumper sticker politics

“Health reform is always more popular as a bumper sticker than as a piece of legislation,” said Larry Levitt, senior vice president for health reform at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

He points to both the Obamacare and the Obamacare repeal efforts as examples — some ideas behind Obamacare, like insuring pre-existing conditions, were popular. But other aspects that proponents said were necessary to make it work, like the individual mandate, infuriated some voters, helping propel Republicans to big wins in 2010.

Likewise, the Obamacare repeal effort fired up many Republican voters, but the implications of the various repeal plans — fewer people with insurance, lack of protections for pre-existing conditions — ultimately helped doom the effort.

Medicare-for-all may prove to be yet another example of this trend, according to Levitt.

“There’s a huge political benefit for candidates to be in favor of the idea of Medicare-for-all in a primary,” he said. “But the more the details get filled in, the less popular that idea will be.”

California Sen. Kamala Harris may be the first to face a big lesson in this. At a recent CNN town hall, host Jake Tapper asked her about her support of Sanders’ Medicare-for-all bill, which he said would “totally eliminate private insurance.”

(A quick note here: Sanders’ plan does not totally eliminate private insurance, but it would vastly diminish its role.)

Harris said that she would eliminate private insurance — but after a quick backlash, the next day clarified, with a campaign spokesman saying she also supports more incremental health care overhauls.

Polling also shows how tricky selling Medicare-for-all could be once the details come into play. A January poll from Kaiser shows that nearly 7 in 10 Americans like Medicare-for-all if they hear it will eliminate premiums and out-of-pocket costs. But that support drops to around 4 in 10 if people hear it will mean higher taxes.

Both of those things could be true of a Medicare-for-all system. But trying to sell even this basic trade-off on the campaign trail — especially this early — is tough.

At the other, more moderate end of the spectrum, Klobuchar said she’s for the broad goal of “universal health care,” and did get specific on her support of a public option. But when it comes to Medicare-for-all, she remained vague, saying it could be a possibility. Voters will almost certainly try to pin her down more on that in coming months, but for now her answer may help keep her from alienating some more liberal voters.

For many candidates, keeping health care rhetoric broad might be a smart move for now, says Nadeam Elshami, former chief of staff to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

“It’s okay for a candidate to say, ‘Look: This is generally what I believe in. But I’m willing to hear first and then get into specifics later, after I have a deeper discussion of this issue,'” he said.

The “socialist” threat

Progressive health care overhauls will also likely feed into one of President Trump’s main attack lines: labeling Democrats as “socialists” as a way of painting them as extreme.

“It’s a surprising development that 10 years after the passage of the Affordable Care Act and after a massive political backlash against it, and a huge effort to defend it, Democrats are in there immediately swerving so hard to an even greater government role for health care,” said Michael Steel, a Republican strategist who worked for former House Speaker John Boehner and Jeb Bush’s 2016 campaign.

Republicans know political backlash well — the backlash to their repeal efforts culminated in the GOP losing the House in 2018. Whatever criticism Trump throws Democrats’ way on health care for 2020, they will likely counter by asking him if he has his own alternative to Obamacare, having failed to fully repeal it.

Until then, Democrats will be doing similar calculations on both health care and a variety of other issues: weighing sweeping, progressive ideas that the president could try to label as “socialist” against incremental policies that might not excite liberal voters — and deciding which choice is most likely to get a Democrat into office.

Voters want sweeping health care changes …maybe

A basic tension underlies Democratic plans to overhauls the health care system: Only 1 in 3 Americans rate health care in the U.S. as “excellent” or “good,” according to Gallup. But at the same time, a large majority — 7 in 10 — view their own personal health care as “excellent” or “good.”

Which is to say, it’s easy to see how voters might want the system massively reformed. In addition, incremental changes that don’t go as far as Medicare-for-all might particularly infuriate progressive voters.

But at the same time, voters will likely bristle if that reform threatens to change their own health coverage, as some major health care overhauls, like Medicare-for-all, might do.

“There is a reason that President Obama’s signature promise on Obamacare was ‘If you like your plan, you can keep it,'” Steel said.

That promise proved untrue — some Americans saw their health care plans canceled under the new Obamacare rules, and Politifact named Obama’s statement the “lie of the year” in 2013.

Should a Democratic candidate’s health care proposal similarly threaten people’s current health plans, it’s a safe bet that it will become a major Republican line of attack.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))