Before turtles are hatched — when they’re just tiny embryos inside their eggs — they may be able to influence whether they will become male or female, according to a study in China. And this could help protect them from the effects of climate change.

Scientists have known that for many reptiles, sex is determined by the temperature an embryo experiences as it grows. In some turtle species, for example, slightly higher temperatures cause the embryo to become female and lower temperatures cause the embryo to become male.

“It’s a strange and wonderful aspect of reptile biology that in many turtles, all crocodiles and quite a few lizards, the sex that an animal develops into is determined by the temperature that it experiences within the nest when it’s inside the egg,” said biologist Rick Shine of Macquarie University in Australia, who worked with Chinese scientists on the study published Thursday in Current Biology.

As temperatures rise because of climate change, there have been reports of virtually no male sea turtles being born in some areas because it’s too hot for males to develop. Populations with far more females than males may have a tougher time reproducing, and therefore surviving.

The researchers involved in this study, led by Wei-Guo Du at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, were curious about how turtles might have survived temperature shifts in the past. And they wondered whether turtle embryos were doing something inside the egg to shield themselves from these shifts.

They focused on the Chinese three-keeled pond turtle, a freshwater turtle native to China and southeastern Asia. At incubation temperatures lower than 78.8 degrees Fahrenheit, according to the scientists, every embryo will be male. And at temperatures higher than 86 degrees, they will all be female.

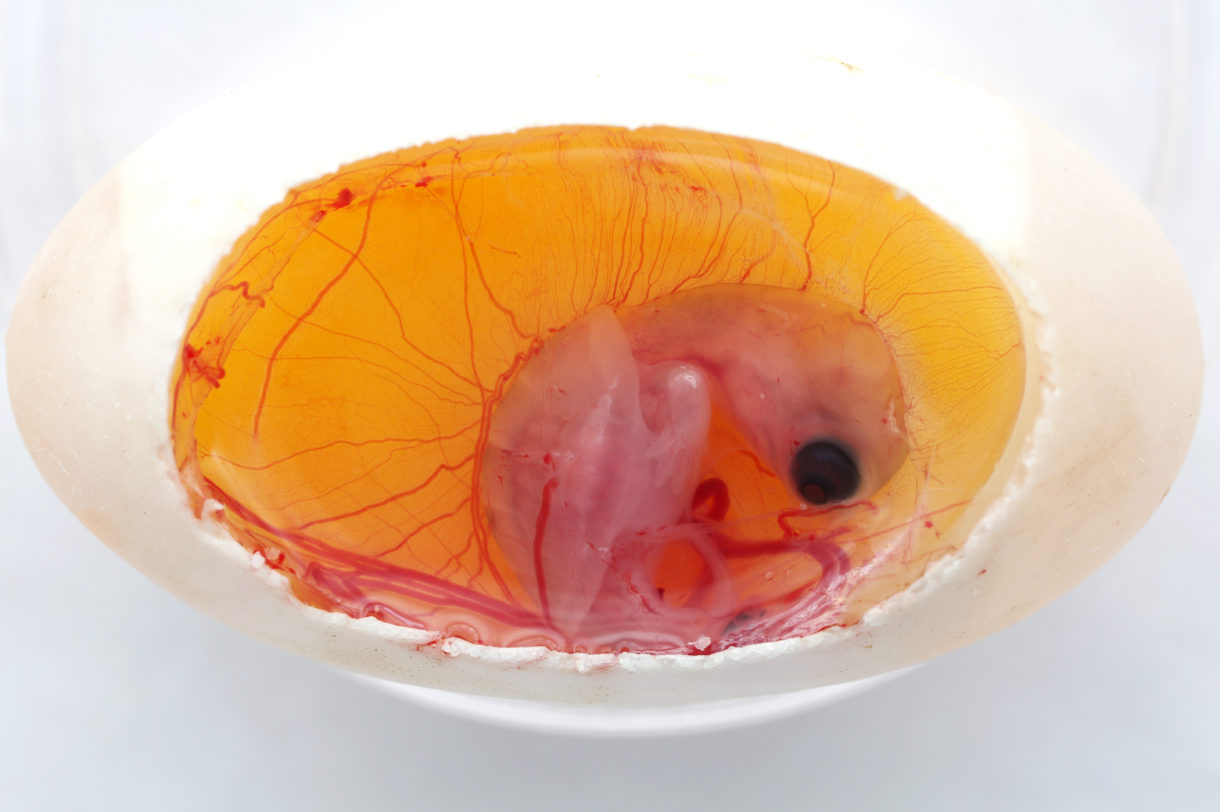

Du had the idea that “perhaps the embryos of reptiles could move around within the egg because it might be a little bit warmer at one end of the egg than the other,” Shine said.

And by moving to a different part of the egg, the researchers wondered, could an embryo could actually influence its sex? Shine said three-keeled pond turtle eggs, which are found in shallow nests where the sun can warm the ground, have areas that are up to eight degrees warmer than the coldest areas.

So scientists collected dozens of eggs in multiple nests and tested them in a variety of temperature conditions. They used a drug called capsazepine to shut down some of the embryos’ ability to sense heat. “Just have to paint it on the egg shell, and you have an embryo inside that’s no longer aware of the temperature differences within the egg,” Shine said.

The embryos in eggs painted with the drug were relatively inactive and took longer to hatch. “They just sat there within the egg,” he said. “They didn’t move in any consistent fashion toward the warm or the cooler spots.” And when the animals emerged from their shells, the chemically treated nests were almost all male at lower temperatures or almost all female at higher temperatures.

The other embryos — the ones still able to sense temperature normally — behaved very differently, he said. They appeared to move more and would hatch with a much more even male-to-female ratio.

“It does seem as if the embryo has a lot more control over its destiny than we ever expected,” Shine said.

This idea is controversial. Biologist Boris Tezak of Florida Atlantic University is skeptical that an embryo would have the muscle strength to move at the point in its development when it could influence its sex. “There are some important gaps in the data that need to be addressed for me to be totally convinced,” he said.

Tezak also wonders whether capsazepine could have unintended effects on sex determination, and not just on an embryo’s ability to sense temperature. Shine said the team’s study took such factors into account.

It’s worth noting that the researchers don’t think the embryos were making a conscious choice to become male or female. “I don’t think the turtle embryos are sitting there making clever calculations or being conscious of any of these things,” Shine said. Moving from one part of an egg to another is more likely an unconscious behavior that the turtles evolved.

He also said the amount of control the embryo has is pretty subtle. It can act as a buffer for small temperature differences, but is no defense against major swings. And in other turtle species, the animals might have less room to move inside an egg and there might be less temperature variation inside it.

Still, Shine said he is “impressed yet again about the resilience of natural systems.”

“These organisms are far more sophisticated than we might think. They’re capable of dealing with all kinds of unpredictable challenges that get thrown at them by the outside world,” he said.

“The danger, of course, is that we’re throwing so many challenges at them, so quickly, that perhaps they may fail to deal effectively with that combination of circumstances that we’re creating.”

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))