In modern medicine, the mind and body often stay on two separate tracks in terms of treatment and health insurance reimbursement. But it’s hard to maintain physical health while suffering from a psychological disorder.

So some Medicaid programs, which provide health coverage for people who have low incomes, have tried to blend the coordination of care for the physical and mental health of patients, with the hope that it might save the state and federal governments money while also improving the health of patients like John Poynter of Clarksville, Tenn.

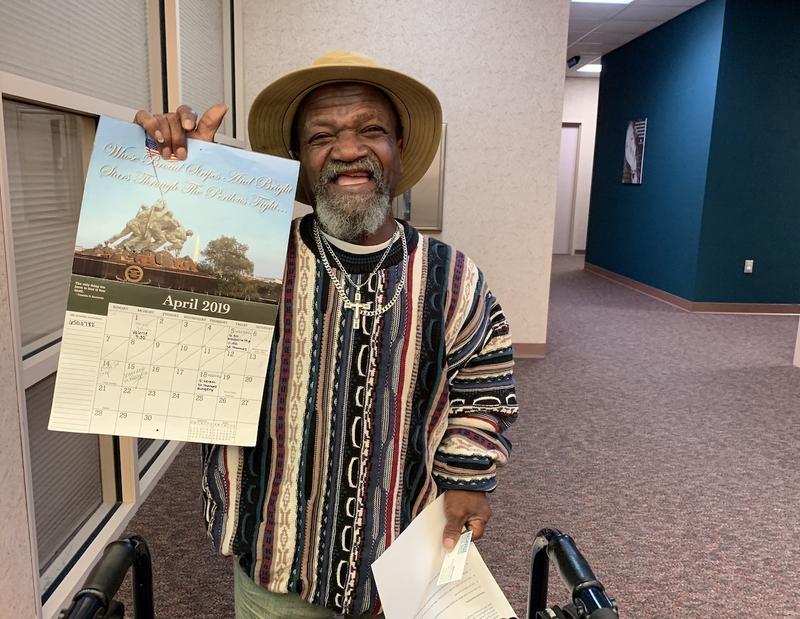

Poynter has more health problems than he can even recall. “Memory is one of them,” he says, with a laugh that punctuates the end of nearly every sentence.

He is currently recovering from his second hip replacement, related to his dwarfism. Poynter is able to get around with the help of a walker — it’s covered in keychains from everywhere he’s been. He also has diabetes and is in a constant struggle to moderate his blood sugar.

But most of his challenges, he says, revolve around one destructive behavior — alcoholism.

“I stayed so drunk, I didn’t know what health was,” Poynter says, with his trademark chuckle.

Nevertheless, he used Tennessee’s health system a lot back when he was drinking heavily. Whether it was because of a car wreck or a glucose spike, he was a frequent flyer in hospital emergency rooms, where every bit of health care is more expensive.

The case for coordination of mind-body care

Tennessee’s Medicaid program, known as TennCare, has more than 100,000 patients who are in similar circumstances to Poynter. They’ve had a psychiatric inpatient or stabilization episode, along with an official mental health diagnosis — depression or bipolar disorder, maybe, or, as in Poynter’s case, alcohol addiction. And their mental or behavioral health condition might be manageable with medication and/or counseling, but without that treatment, their psychological condition is holding back their physical health — or vice versa.

“They’re high-use patients. They’re not necessarily high-need patients,” says Roger Kathol, a psychiatrist and internist with Cartesian Solutions in Minneapolis, who consults with hospitals and health plans that are trying to integrate mental and physical care.

As studies have shown, these dual-track patients end up consuming way more care than they would otherwise need.

“So, essentially, they don’t get better either behaviorally or medically,” Kathol says, “because their untreated behavioral health illness continues to prevent them from following through on the medical recommendations.”

For example, a patient’s high blood pressure will never be controlled if an active addiction keeps them from taking the necessary medication.

But coordinating mental and physical health care presents business challenges — because, usually, two different entities pay the bills, even within Medicaid programs. That’s why TennCare started offering incentives to reward teamwork.

Health Link

TennCare’s interdisciplinary program, known as Tennessee Health Link, was launched in December 2016. The first year, the agency paid out nearly $7 million in bonuses to mental health providers who guided patients in care related to their physical health.

TennCare has a five-star metric to gauge a care coordinator’s performance, measuring each patient’s inpatient hospital and psychiatric admissions as well as visits to emergency rooms. Providers are eligible for up to 25% of what’s calculated as the savings to the Medicaid program.

Studies show this sort of coordination and teamwork could end up saving TennCare hundreds of dollars per year, per patient. And a 2018 study from consulting firm Milliman finds most of the savings are on the medical side — not from trimming mental health treatment.

Savings from care coordination have been elusive at times for many efforts with varying patient populations around the U.S. A TennCare spokesperson says it’s too early to say whether its program is either improving health or saving money. But already, TennCare is seeing these patients visit the ER less often, which is a start.

While there’s a strong financial case for coordination, it could also save lives. Studies show patients who have both a chronic physical condition and a mental illness tend to die young.

“They’re not dying from behavioral health problems,” points out Mandi Ryan, director of health care innovation at Centerstone, a multistate mental health provider. “They’re dying from a lack of preventive care on the medical side.”

“So that’s where we really started to focus on how can we look at this whole person,” Ryan says.

But refocusing, she says, has required changing the way physicians practice medicine, and changing what’s expected of case managers, turning them into wellness coaches.

“We don’t really get taught about hypertension and hyperlipidemia,” says Valerie Klein, a care coordinator who studied psychology in school and is now an integrated care manager at Centerstone’s office in Clarksville, Tenn.

“But when we look at the big picture,” Klein says, “we realize that if we’re helping them improve their physical health, even if it’s just making sure they got to their appointments, then we’re helping them improve their emotional health as well.”

Klein now helps keep Poynter on track with his treatment. Her name appears regularly on a wall calendar where he writes down his appointments.

Poynter calls Klein his “backbone.” She helped schedule his recent hip surgery and knows the list of medications he takes better than he does.

Klein acknowledges it’s a concept that now seems like an obvious improvement over the way behavioral health patients have been handled in the past. “I don’t know why we didn’t ever realize that looking at the whole person made a difference,” she says.

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with Nashville Public Radio and Kaiser Health News.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))