“I was both an observer and a participant in a teenage rape.”

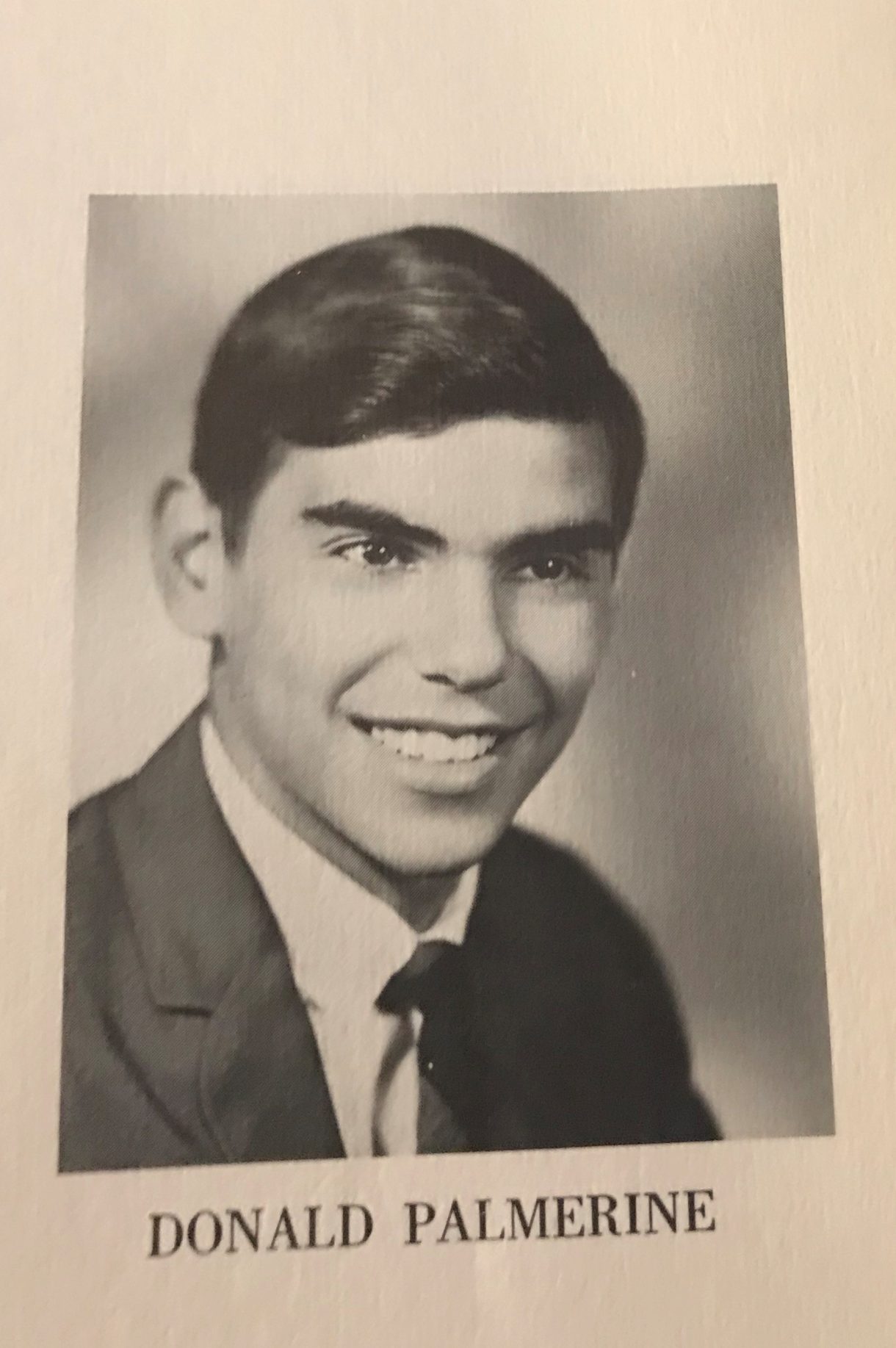

That sobering confession is how Don Palmerine began to tell his story publicly for the first time, at age 67, in a Washington Post essay published earlier this month about the part he played in a sexual assault.

Palmerine was a 17-year-old high school student when he attended a party and, according to his account, watched through a window as a young man raped a young woman. That was in 1969. As he described the incident in The Post:

At one point, a boy told several of us to go outside and look through a window into the basement because another boy, a football player, had taken a girl there. (There were far more boys than girls at this party.) When we peered through, we saw the girl passed out on a sofa, her feet facing us. As the boy approached her, he waved to us, smiling. He proceeded to remove her jeans and then her underwear. It was the first time I had seen a girl naked. He climbed on top of her and penetrated her. She immediately woke up and tried to fight him off. At this point, we all scattered in the yard. No one said anything. There was just nervous laughter.

Eventually, we all went back into the house. I don’t remember anyone drinking, other than the girls. I did not drink anything. We must have gone into a bedroom, because the next thing I recall is standing with about 10 other boys around a bed on which a different girl had passed out. Everyone was touching her through her clothing. I placed my hand on her leg and quickly removed it.

One boy kept turning the lights on and off. When they came on, everyone removed their hands from the girl’s body. In the dark, everyone put their hands back on her. Everyone would laugh. It was some kind of game, and we all seemed to understand the rules. This happened four times, and then we all left the room. I’m glad it didn’t go further.

Over the next 50 years, Palmerine says, he did nothing and said nothing. But the guilt stayed with him.

It wasn’t until he watched Christine Blasey Ford testify before the Senate judiciary committee last month that he felt he needed to speak up.

His experience, he says, felt akin to the incident Ford described in which she says now-Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh assaulted her when they were in high school. (Kavanaugh has vehemently denied the allegation.)

“I felt it was genuine, and I felt she was really telling the truth,” Palmerine tells NPR’s Michel Martin. Palmerine also writes that, Like Ford, he struggles to remember key details about the evening:

I don’t remember the month it occurred or the exact town it was in, but I remember that the party was in an upper-class suburb south of Pittsburgh. I don’t remember how I got home. These details don’t matter to me. What I remember clearly was the rape. Recalling it, for me, is like remembering where I was when I found out that President John Kennedy had been assassinated. There is a before and an after.

But he also wanted to forget about the event, he says, which kept him from coming forward. “When you’re guilty about something, you don’t want to tell anyone … I did something bad, I said in the article I committed a crime, and I did.”

In the past year, the #MeToo movement has brought worldwide attention to stories about women and men who have survived sexual assault. And while some high-profile men have been convicted of their sexual assault crimes, rarely have men come forward about witnessing or playing a role in sexual abuse.

“I wanted to tell this story because I believe it’s time for men to tell the truth about the ways they’ve abused women and what our role has been in creating a culture that tolerates this,” Palmerine says.

He also writes that he wonders about how that night shaped the lives of those young women at the party — “If they remember this night. If they told their daughters.”

He writes:

In 1969, there was nobody to turn to. They certainly wouldn’t have gone to the police — at the time, a subtle notion persisted that an assault was always the girl’s fault, that she shouldn’t have gotten herself into that position in the first place. They wouldn’t have told their parents, who would probably have scolded them.

As for the men, he says, he’s unsure why they’ve been silent. “I think men should be part of the #MeToo movement. I think we should come forward and talk about what we’ve seen, what we’ve done — I think that should be part of it.”

After talking to his wife and three sons (ages 11, 17 and 19) about what he had witnessed when he was 17, he decided to write about it for The Post. But he hadn’t told his wife about his participation in assaulting a woman later that night. “She didn’t know that until this [Washington Post] article came out,” he says. “It was tough for her to take.”

Palmerine says his sons showed him comments from people who responded to his story on Twitter. “It’s almost as if I was the first guy to admit this,” he says.

As Palmerine wonders about what happened to those women, he says, “The only thing I can say [to them] is I’m sorry. I didn’t help.”

“You know, a few women called me a hero, but no, I wasn’t,” he says. “I would’ve been a hero if I helped these women then.”

NPR’s Gemma Watters and Rachel Gotbaum produced and edited the audio version of this story. Emma Bowman adapted it for the Web.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))