Imagine if President Trump, on the weekend after the upcoming midterm elections, suddenly forced out Jeff Sessions, Rod Rosenstein and Robert Mueller.

For the record, that would be the removal of the attorney general, the deputy attorney general and the special counsel investigating Russian interference in the 2016 election.

And imagine Trump also shut down the offices occupied by Mueller’s team of prosecutors — lock, stock and barrel.

Just like that.

Impossible, you say? Unprecedented? In fact, it is neither.

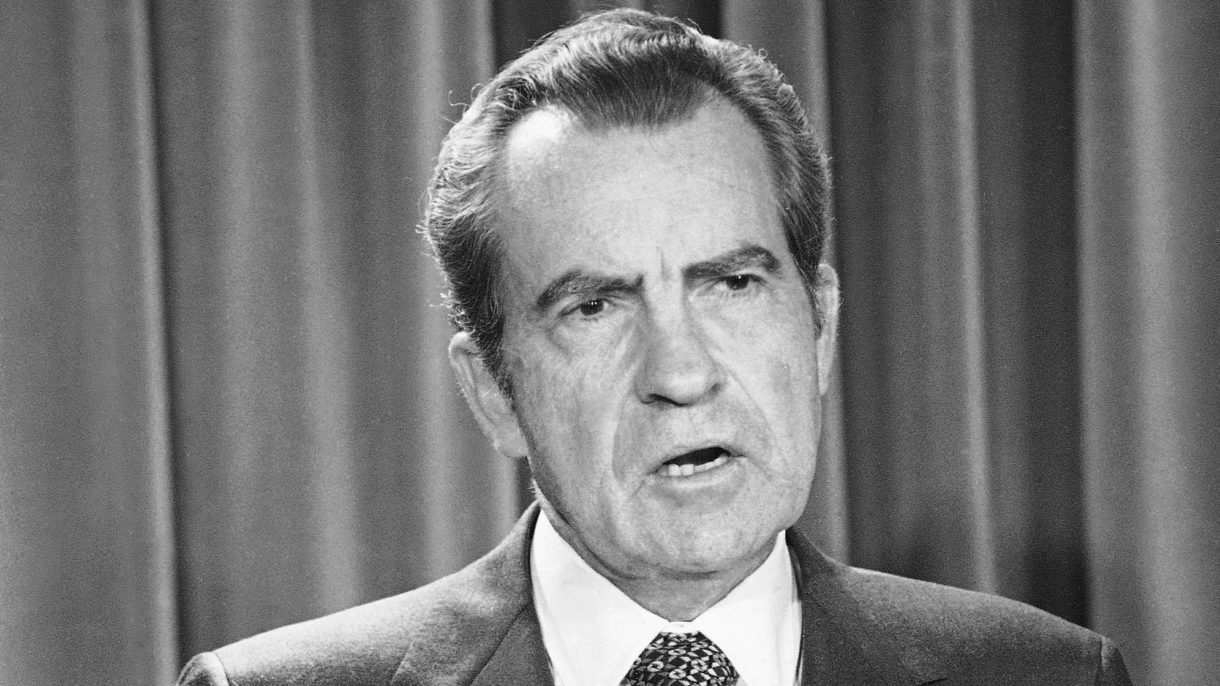

It is the scenario Washington, D.C., witnessed exactly 45 years ago this weekend, when President Nixon lost patience with his own Justice Department’s relentless investigation of the Watergate case — a case that would eventually bring about Nixon’s resignation.

Nixon’s firing spree was soon dubbed the Saturday Night Massacre. And, by that name, it has remained notorious enough to be mentioned whenever a president seems to be contemplating serial firings.

In Trump’s early months in office, his removal of an acting attorney general (Sally Yates) and the director of the FBI (James Comey) drew comparisons to the infamous Saturday in 1973.

Trump has made manifest his unhappiness with Sessions, who recused himself from the Russia investigation, leaving Rosenstein to take it over. The president has recently held more than one personal meeting with Rosenstein, who has increasingly been regarded as a target of Trump’s distrust since he appointed Mueller.

On the job now for about a year and a half, Mueller has prosecuted a number of Russian officials and several Americans — winning several convictions and guilty pleas with agreements to cooperate. These include Paul Manafort, who was briefly Trump’s campaign chairman in 2016 and will be sentenced in February.

Trump has restrained his famous penchant for firing close associates, at least so far. But if the approaching midterms are a factor in his thinking, that restraint might be coming to an end with Election Day on November 6.

There were no midterms looming for Nixon in October 1973. He was trying to deal with a bout of economic troubles and a hot war in the Middle East. (Dubbed the Yom Kippur War, the fighting had begun earlier in the month and Israel had come close to being overrun.)

But he also was trying to rid himself of the lingering cloud of a scandal from the year before, and he may have thought the busy news docket of that weekend made it the perfect time.

To review the state of affairs that fall: It all began when five men were arrested after breaking into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee, an office inside the Watergate hotel complex.

That incident happened in June 1972 during the president’s re-election campaign, and the burglars were later found to have ties to that campaign. In fact, their escapade that night had been part of a far larger scheme of espionage and sabotage against Democratic candidates. Much of this was revealed by two young investigative reporters for The Washington Post named Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

Despite these early revelations, Nixon was re-elected in November of that year, carrying 49 of the 50 states. So it was amazing that in the first months of 1973, his presidency began to sag under the weight of Watergate.

It turned out the White House and the president had been involved in obtaining “hush money” for the burglars. This led to the sudden departure of Nixon’s chief of staff, top domestic adviser and White House counsel. Nixon had also fired his previous attorney general, replacing him with a longtime backer and Republican loyalist named Elliot Richardson.

The summer had featured weeks of televised hearings by a special Senate investigating committee. Among other things, the viewing public saw former White House counsel John Dean testify that he had told the president of a cancer growing on the presidency.

Audiences also heard a White House aide reveal that all conversations in Nixon’s Oval Office were recorded and preserved on tape. The senators wanted to hear the tapes. So did Archibald Cox, a law professor who had been tapped by Richardson to be a Justice Department special prosecutor and sort out the Watergate imbroglio once and for all.

Nixon did not want to hand over the tapes. Cox got a subpoena. Negotiations dragged on; some tapes were released and others were withheld. After weeks of standoff, Nixon tired of the confrontation. So on that Saturday afternoon, Oct. 20, 1973, he ordered Richardson to fire Cox.

Richardson was deeply disturbed by the dilemma and refused to fire the man he had chosen. Richardson resigned instead. His deputy, William Ruckelshaus, also an establishment Republican of long standing, also refused to fire Cox and resigned.

Nixon summoned his solicitor general, whose job was usually presenting arguments for the administration in cases before the Supreme Court. As the third-ranking official in the Justice Department, that man was now the acting attorney general. Nixon told him to fire Cox, and he did so.

(His name was Robert Bork, and 14 years later the Senate would refuse to confirm him for a seat on the Supreme Court after a highly contentious review process in which the memory of his firing of Cox was a factor.)

But going back to October 1973, it was still Saturday night, and the nation suddenly saw news anchors’ faces interrupting their entertainment programs — repeating the facts of the firings with a mix of solemnity and disbelief. Correspondents, including a very young Tom Brokaw on NBC, stood outside the White House reading from carefully worded scripts.

By that time, FBI agents had appeared at the special prosecutor’s office to remove boxes and lock the doors. Members of Cox’s investigative team were there, captured by TV camera crews milling in the halls in a state of surprise and confusion.

Confusion would reign for some time to come. Members of Nixon’s inner circle had convinced themselves the Cox investigation could be ended with minimal public concern. They could not have been more mistaken. The firings dominated the news, despite the important foreign and domestic stories of the day. Congress, controlled in both chambers by Democrats, renewed its efforts to obtain the tapes.

Most importantly, Nixon was pressured by his party to appoint a new special prosecutor in Cox’s place. He named Leon Jaworski, a loyal Republican from Texas who had told friends he never made much of the whole Watergate affair until the night of the Saturday Night Massacre.

Jaworski would surprise many by digging in and pursuing the tapes and other elements of the Watergate case with dogged determination. His work eventually forced the confrontation over the tapes all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled unanimously against Nixon’s claim of executive privilege.

About the same time, in late July 1974, the House Judiciary Committee approved the first of three articles of impeachment against Nixon for consideration by the whole House. Approval there was assured. Republican senators sent a message to the White House. The necessary two-thirds majority required to remove Nixon from office was already a reality.

On August 9, 1974, Nixon became the only U.S. president to resign.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))