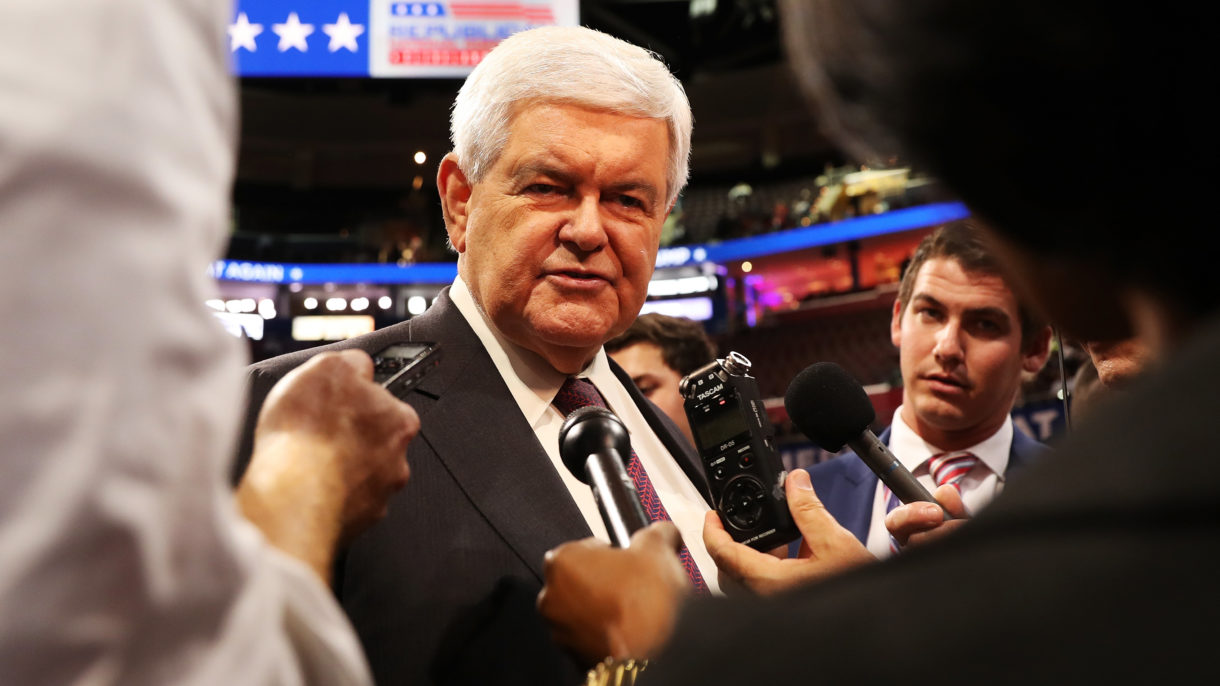

Partisan combat has always been a part of American politics, but Atlantic journalist McKay Coppins traces many of the extreme tactics used today to one man: former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich.

When Gingrich entered Congress in 1979, the Georgia Republican rejected bipartisanship and “turned national politics and congressional politics into team sport,” Coppins says.

While in Congress, Coppins says Gingrich treated politics as a “zero-sum” endeavor — and he wasn’t above resorting to name-calling, conspiracy theories and strategic obstruction in order come out on top: “He was not there to work in the committee structure and deal with constituent services. He was there to foment revolution and declare war.”

Though Gingrich left Congress 1999, his aggressive tactics have had a lasting impact. Coppins writes about how the former speaker helped paved the way for Donald Trump’s election in his Atlantic article, “The Man Who Broke Politics.”

“He set a model for future Republican leaders,” Coppins says of Gingrich. “I think that his defining legacy is he enshrined this combative, tribal, angry attitude in politics that would infect our national discourse in Washington and Congress for decades to come.”

Interview Highlights

On how Newt Gingrich reshaped Congress into the partisan body it is today

His career is important to understand if you want to understand how we got to this point in our politics. … If you look at the way that [Gingrich] gained power in the first place, he did it very deliberately and methodically by undermining the institution of Congress itself from within, by kind of blowing up the bipartisan coalitions that had existed for a long time in Washington and then using the kind of populist anger at the gridlock in Congress to then take power. And that’s a strategy we’ve seen replicated again and again, all the way up into 2016 when Trump was campaigning on draining the swamp. This is a strategy that may seem kind of commonplace now but that Newt Gingrich was one of the premier architects of.

On how Gingrich sees politics as a battle

Prior to entering Congress, Newt Gingrich had been a historian. He had a Ph.D. in history. He was teaching history at West Georgia College, and he kind of gravitated toward heroes of war more than anything else. He loved reading war histories [of] World War I, World War II. In fact, one of the defining moments of his life, according to him, was when he was 15 years old and he visited a battleground in Verdun, France, with his with his parents and toured the grounds and it was this very macabre setting where there [was] an ossuary where there were bones piled high from dead soldiers, and it was still scarred by cannon fire. He told me that that was an important moment where he realized, in his words, “that countries can die,” and that it would be his role to make sure that America didn’t.

He’s always kind of framed his role in politics as that of a figure in war or at battle. He doesn’t kind of look to the great legislators or deal-makers or politicians, for the most part, as his role models; he looks to generals and warriors.

On how Gingrich went about creating a new kind of Republican to run for the House

This just isn’t a story of ideology, it’s also a story of kind of attitude and style and tactics. Most of the congressmen that Gingrich helped elect or kind of gave power to were more conservative, but they were also — for lack of a better word — meaner and more aggressive and more combative and more confrontational. …

Gingrich had this organization called GOPAC that he used to provide training to Republican candidates who wanted to emulate Newt Gingrich. He would send out cassette tapes and memos to these candidates providing them with kind of attack lines and and talking points and frankly created a whole new vocabulary for this rising generation of conservatives.

There was one memo I write about in the piece called “Language: A Key Mechanism of Control,” that literally included a list of recommended words that Republicans should use in describing Democrats. And they included words like “sick,” “pathetic,” “lie,” “anti-flag,” “traitors,” or “radical” and “corrupt.” …

The kind of broader strategy when waging these national campaigns was to reframe the kind of policy debates in Washington that may have seemed kind of dull or inaccessible to the average American and turned them into these big struggles between good and evil, or white hats versus black hats, and a battle for the character and soul of America.

On how Gingrich worked outside of the established Republican infrastructure

His tactics, strategy was to build his own infrastructure entirely outside of the Republican institutions. So he went out himself and raised money. He went out himself and recruited candidates. Some of the candidates that he backed were explicitly Republicans that most establishment figures in Washington did not want to see in Congress, but he didn’t care. He kind of saw his role as building a new Republican Party outside of the existing infrastructure. … And certainly Donald Trump was able to win the Republican nomination without any institutional support at first by kind of following the same tack.

On how Gringrich pioneered the use of C-SPAN for political advantage

Gingrich recognized the potential political value in the C-SPAN cameras that had just recently been installed in the House at the time that he was kind of rising up through the ranks. He would kind of take to the floor at the end of the day when the chamber was basically empty, and he would give these kind of thundering speeches, kind of tirades against the Democrats, that were being delivered to no real audience in the actual room where he was, but that were then being beamed out to televisions across the country. He found that the more provocative he was and the more angry he was, the more likely his speeches were to get picked up in the news.

On Gingrich losing his speakership and resigning in 1999

On the way out the door, there’s this great quote where he says, “I’m willing to lead, but I’m not willing to preside over people who are cannibals.” I think, like a lot of revolutionaries — or people who see themselves as revolutionaries — they’re great at gaining allies early on and turning it into a movement and gaining power, but then they’re not always great at using that power to achieve the agenda that originally got them to where they were. And so Gingrich did end up kind of getting driven out by the same bloodthirsty brigade of right-wing lawmakers that he helped elect in the first place.

On how Democrats in the Trump era are also using Gingrich tactics

Gingrich’s tactics began with the Republican Party, and to a certain extent, the Republican Party ever since Gingrich has been much better at wielding them. But you do increasingly, in the Trump era now, see Democrats kind of saying that: “We need to take cues from Newt Gingrich. We need to take cues from the Republican Party if we want our agenda to be taken seriously, we need to take this war for power ethos that Gingrich enshrined and play by those same rules, or we’ll never get we’ll never get our priorities passed and we’ll never be able to kind of beat back Trump and his Republican allies.”

Amy Salit and Mooj Zadie produced and edited the audio of this interview. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Dana Farrington adapted it for the Web.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))