It used to be you would sign on the bottom line, whether it was a check or a credit card receipt or even a love letter. But the art of the signature has become less important and less practiced, and that has meant less certainty for elections officials in several states who are still counting votes from the Nov. 6 midterm elections.

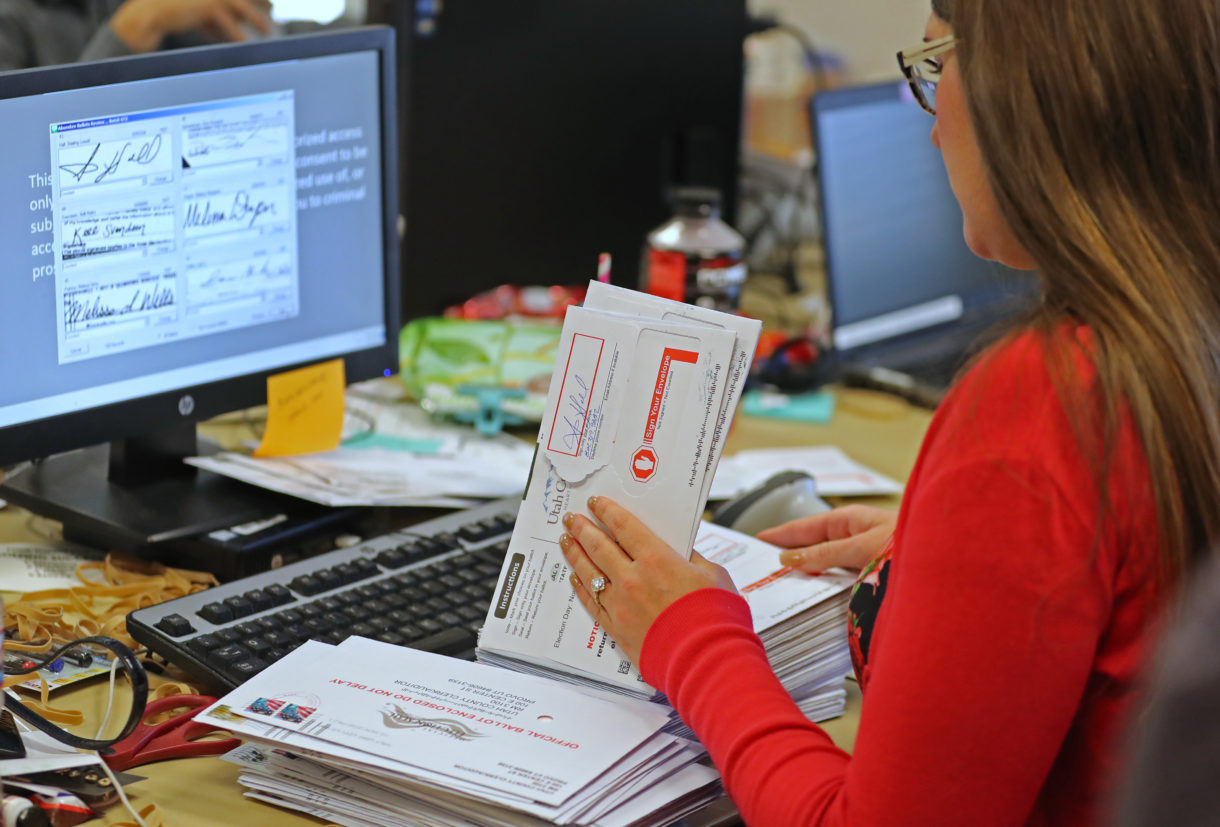

Those officials are trying verify that the signatures required on mail-in, provisional, absentee and military ballots match the signature that voters have on file with the board of elections.

But signatures change over time — a problem especially for younger voters, says Daniel Smith, a professor and chair of the political science department at the University of Florida.

“Let’s say you’re a civically engaged 16-year-old and you preregister to vote in Florida, which you are allowed to do,” Smith tells NPR. “You might have a signature that has a nice heart over the ‘i’ in your name as a 16-year-old, but you come to the University of Florida, you become a sophisticated Gator, and your signature now looks very different.”

Smith, who authored a study on the issue for the American Civil Liberties Union of Florida, says it’s the signature that the voter created at 16 that is going to be the signature of record.

That causes problems with younger people, “whose signatures are not fixed in a digital world, where you’re signing your name with your finger on an iPad,” Smith says. That could disenfranchise young voters, which he says is “somewhat incompatible with the right to vote.”

If the signature of record does not match the one on the most recent ballot, that vote could be flagged and potentially not counted.

Smith says his study found that younger voters were four times more likely to have their absentee ballots rejected than voters older than 65, whose signatures are pretty well set.

Another issue, he says, is many elections officials aren’t well-trained in how to compare signatures.

“You can’t just match a signature with one other signature and have any confidence that it’s the same individual who has written both of them,” Smith says. “You need to have a range of different signatures,” he says, because signatures vary “depending on the condition in which they’re writing the signature, the type of pen they’re using, whether they’re doing it inside or outside.”

In Colorado, where every voter receives a mail-in ballot, officials are well trained in how to read signatures. In Denver, former elections director Amber McReynolds says, the county election board brought in a handwriting expert to develop training materials.

“He would come in every election cycle and train the judges on what to look for, how to approach signature verification — all that,” says McReynolds, now executive director of the National Vote at Home Institute and Coalition.

McReynolds says most big counties in Colorado use signature software that is more consistent than human eyes. The biggest issue, she says, is whether there is enough time allotted for voters whose signatures don’t match to fix any discrepancies before the deadline for ballots to be counted.

Most states with good processes “allow that to happen usually eight to 10 days postelection,” she says, “so that voters can return the affidavit and the other required elements to make sure that their ballot does count.”

In Washington state, counties have three weeks to count ballots, as long as they were postmarked by Election Day; in California, officials have a month to finish their work.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))