Nearly 200 countries have agreed on a set of rules to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions, a crucial step in implementing the landmark 2015 Paris climate agreement.

The rules describe in detail how countries will track their emissions and communicate with each other about their progress in the coming years and decades. But it stops short of committing them to the more ambitious emissions reductions necessary to slow climate change.

The meeting in the heart of Poland’s coal country unfolded in the shadow of a stark scientific reality about the threat posed by rising temperatures and in the midst of global political upheaval. In the months leading up to the meeting, a series of reports from the world’s scientists showed that global emissions are not just continuing to rise, but that nations are not on track to limit the rise of global temperatures enough to avoid the most catastrophic effects of climate change.

On the political front, President Trump says he intends to withdraw the U.S. from the Paris agreement and has engaged China in a trade war; Brazil’s new president-elect has signaled he may no longer support the agreement; and leaders in Europe are struggling with domestic challenges, including the recent “Yellow Vest” protests in France over fuel taxes.

In that context, some observers were cautiously optimistic about the outcome of this week’s U.N. climate talks in the city of Katowice. “Particularly given the broader geopolitical context, this is a pretty solid outcome,” said Elliot Diringer, the executive vice president of the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. “It delivers what we need to get the Paris Agreement off the ground.”

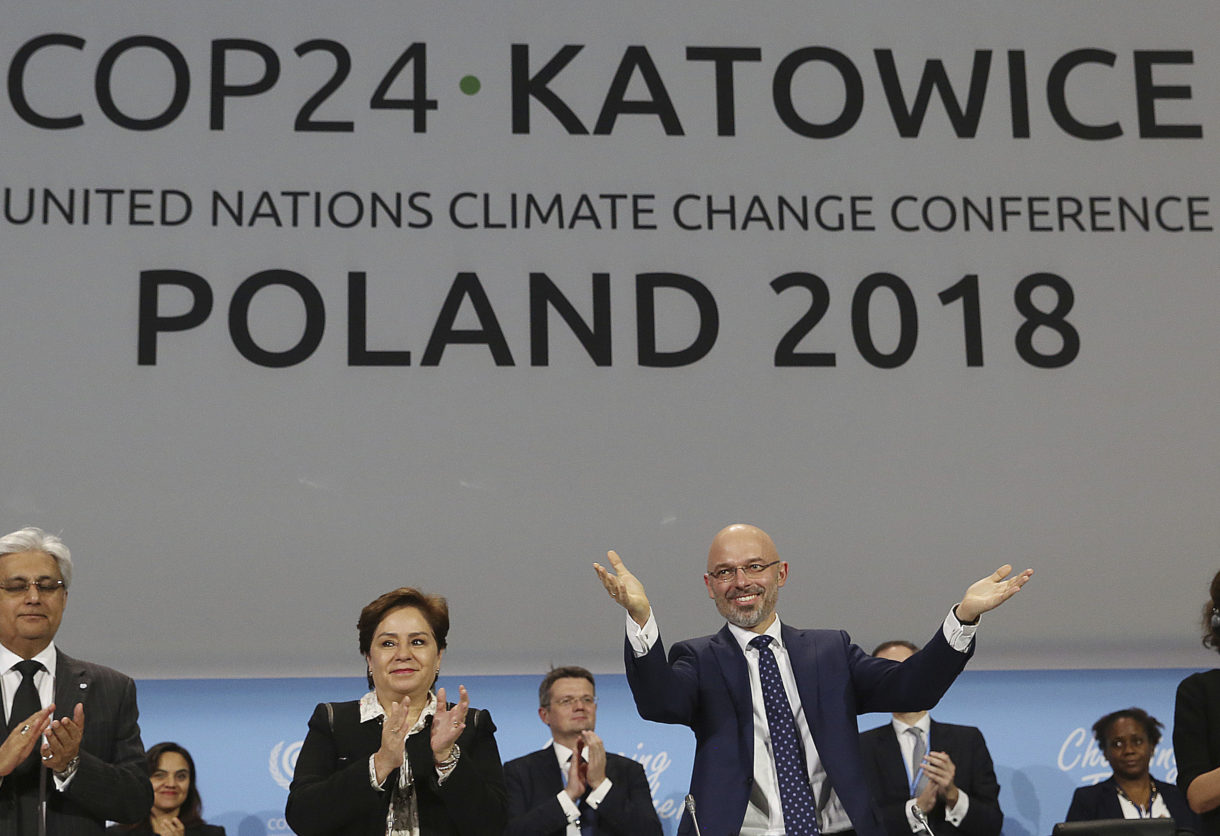

The leader of the meeting, Polish official Michal Kurtyka, noted in his final speech to delegates that it was difficult to get nearly 200 countries to agree on specific rules. Even one step forward is an achievement, he explained, and “you have made a thousand little steps forward. You can be proud.”

One of the most fundamental parts of the so-called rule book negotiated at the talks is a section on transparency, which governs what information governments must disclose to each other about their greenhouse gas emissions. Not all countries agreed going into the talks about how much information they should be required to share about their progress — and as a result, the inner workings of their economies.

The final rules set a timeline for countries to update each other, and includes highly technical guidelines for what types of information they must provide, such as sources of emissions and explanations of their internal analyses.

“The most significant part is the transparency guidelines, which put the meat on the bones of that section of the Paris agreement,” says Sue Biniaz, the former top climate lawyer for the U.S. State Department and one of the negotiators who worked on the Paris agreement. “It’s way more extensive than one might have imagined even a few weeks ago.”

But the talks also left many issues unresolved, including whether countries will commit to transitioning even more quickly to clean energy sources, and how much richer countries will help poorer countries pay for that transition.

United Nations Executive Secretary Patricia Espinosa, reading a statement on behalf of the U.N. Secretary-General, spoke bluntly about the need for countries to move more quickly to curb greenhouse gas emissions. “From now on, my top five priorities will be ambition, ambition, ambition, ambition, ambition,” she said.

The U.N is hosting a special follow-up climate meeting next September.

Many of the most vulnerable nations in the world, including islands, left the meeting in Poland frustrated. In its final statement after the rules had been agreed to, the Malaysian government noted that Western Europe and North America have been industrialized far longer than many parts of Asia, and have profited while contributing enormously to climate change.

The Malaysian delegation called for more money to flow from countries like the U.S. — the world’s largest economy and the second largest polluter — to help pay for damage caused by climate change, saying, “We owe this to the poor and vulnerable who are paying sometimes with their lives in our part of the world.”

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))