This year has been a dismal one for ethics in Washington. Even without a repeat of the 2017 tide of sexual harassment cases in Congress and not counting the results of the Mueller investigation, the D.C. “swamp” remains as stagnant as ever.

It was a year when President Trump pushed out three of his own Cabinet officers over ethics concerns: Secretary David Shulkin at the Department of Veterans Affairs, Secretary Ryan Zinke at Interior and Administrator Scott Pruitt at the Environmental Protection Agency.

Shulkin ran into trouble first, over the winter. Lawmakers faulted him for vacationing, on the government’s tab, in between two important conferences. He was apologetic, telling a House committee, “I do recognize the optics of this are not good. I accept responsibility for that.”

Colorado GOP Rep. Mike Coffman snapped back at that: “It’s not the optics that are not good. It’s the facts that are not good.”

Besides the travel issue, another factor was at play here. Shulkin had been resisting as the administration pushed to privatize some veterans services. He told NPR after his dismissal that political adversaries in the White House kept him from defending himself in the travel scandal.

Trump’s nominee to succeed Shulkin was an unlikely pick: the president’s personal physician, Navy Rear Adm. Ronny Jackson.

He withdrew when senators started questioning his professional behavior, including accusations that he oversaw a hostile work environment and of alleged malfeasance. Finally Trump himself ushered Jackson out the door by bad-mouthing the job. He told reporters, “Adm. Jackson, Dr. Jackson is a wonderful man. I said to him, what do you need it for?”

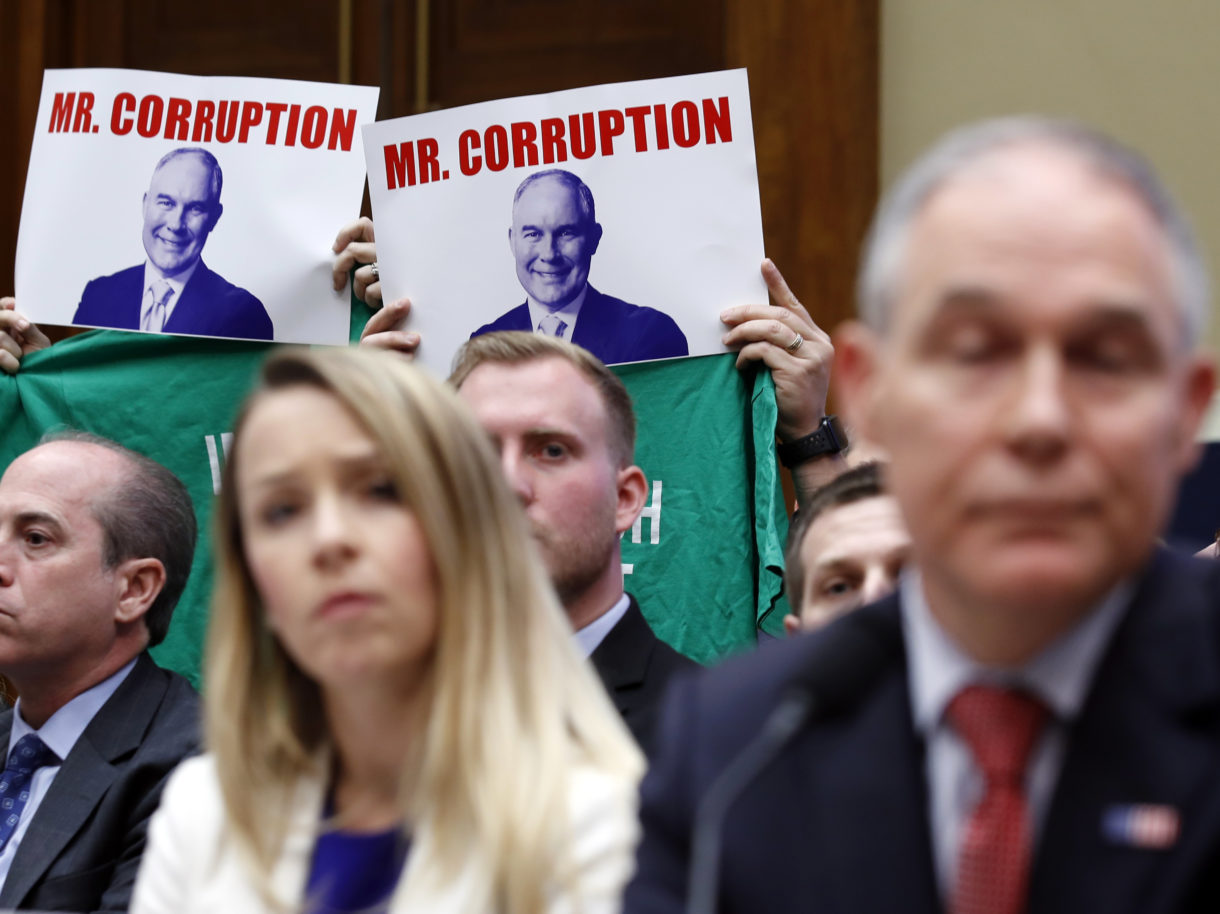

Meanwhile, Pruitt set off more than a dozen ethics investigations. Among the issues: flying first class against federal regulations; using his 24-hour security detail — itself an unusual arrangement for Cabinet officers — to run errands or take him across town with sirens and lights going; constructing a soundproof booth built in his office, costing $43,000; and even trying to buy a used mattress from Trump’s hotel near the White House.

Pruitt, in an interview with Ed Henry of Fox News, said he was under attack because he was so effective. With the changes he brought to EPA, he said, “worldviews clash. Individuals don’t like it, particularly the environmental left. Those groups had their reign at this office and this agency before we arrived. That’s clearing the swamp.”

After Pruitt’s departure, the most intensely investigated Cabinet member was Zinke. Allegations against him included the use of a federally chartered airplane for nonofficial travel and possible conflicts of interest in a land deal between a foundation founded by Zinke and a development project involving the chair of the oil services company Halliburton.

Zinke’s final error may have come in late November. Arizona Rep. Raúl Grijalva, a Democrat, wrote that Zinke should resign immediately, and Zinke tweeted about Grijalva, “It’s hard for him to think straight from the bottom of the bottle,” without explanation.

Zinke sent the tweet Nov. 30. Trump announced Zinke’s resignation Dec. 15. Grijalva is expected to become chair of the House Natural Resources Committee, which oversees the Interior Department, in January.

Law professor Kathleen Clark, who studies ethics in government at Washington University in St. Louis, said the procession of problematic appointees, combined with the administration’s other ethical problems, lead to a clear conclusion: “The tone from the top in this administration is quite clear. And it’s contempt for ethics standards.

In Congress this year, the Republican majorities in both the House and Senate did little to probe ethical lapses in the administration. At the same time, federal prosecutors charged two GOP congressmen with crimes.

California Rep. Duncan Hunter, a Republican who represents much of San Diego County, was indicted in August, along with his wife, Margaret. The indictment indicates the couple’s lifestyle outstripped his congressional salary, alleging the Hunters used campaign money for everything from dental work to a European vacation and private school for their children.

Hunter laid it all on his wife, telling Fox News that she handled the finances and “whatever she did, that’ll be looked at too, I’m sure. But I didn’t do it.”

The other indicted congressman is Rep. Chris Collins, from far-western New York State. He’s charged with using and sharing inside information about a pharmaceutical developer, in which he was among the largest investors and a board member. He quickly denied the allegations, telling reporters, “The charges that have been levied against me are meritless, and I will mount a vigorous defense, in court, to clear my name.”

Collins and Hunter were the first members of Congress to endorse Trump during the 2016 campaign, and they both won re-election in their staunchly Republican districts in 2018.

Clark said those outcomes highlight a problem: “the weakness of elections as a mode of accountability.”

Democrats are not without their own problems. New Jersey Sen. Bob Menendez was re-elected in the wake of a corruption trial, which resulted in a hung jury but also a unanimous, bipartisan rebuke by the Senate ethics committee.

Still, the party used ethics as a campaign issue during the midterms, something that has brought Democrats success in the past.

House Democrats have pledged to deliver more ethics accountability — in the Trump administration and in the House itself — when they take charge next month. In addition to investigations, they plan to make an anti-corruption package the first piece of legislation introduced in January.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))