When people seek help at a drug treatment center for an opioid addiction, concerns about having contracted hepatitis C are generally low on their list.

They’ve often reached a crisis point in their lives, says Marie Sutton, the CEO of Imagine Hope, a consulting group that provides staff training and technical assistance to facilitate testing for the liver-damaging virus at more than 30 drug treatment centers in Georgia.

“They just want to handle [their drug problem],” Sutton says. “Sometimes they don’t have the bandwidth to take on too many other things.”

And although health care facilities that serve people who use drugs are well-positioned to initiate screening, studies show that often doesn’t happen.

It’s an enormous missed opportunity, say public health specialists.

“It’s a disease that can be cured the moment we identify somebody,” says Tom Nealon, president and CEO of the American Liver Foundation. “Not testing is incomprehensible when you look at what hepatitis C does to their bodies and their livers.”

As the number of people who inject drugs has soared, the rate of infection with hepatitis C — which is frequently tied to sharing needles — has climbed steeply, too.

People with a hepatitis C infection can go for years without symptoms, so may have no inkling they’re sick. That delayed onset makes screening important, say health researchers, since infected people may unwittingly infect others.

Still, while screening people who misuse drugs can break the cycle of transmission, public health advocates say a number of obstacles — a lack of money, staff or other resources — may keep substance abuse facilities from going that route.

“Reimbursement rates for hepatitis C testing often don’t match the cost,” says Andrew Reynolds, hepatitis C and harm reduction manager at Project Inform, a advocacy group for patients. If people test positive, they need to be linked to treatment, and financial support for staffing to do that is often limited, he says.

Only 27.5 percent of 12,166 substance abuse facilities reported offering testing for hepatitis C in 2017, according to research published on the blog for the journal Health Affairs in October. It was one of the first studies to look at this issue since the federal government began reporting on testing for HIV and hepatitis C in its national survey of substance abuse and treatment services in 2016.

When researchers narrowed their analysis to the much smaller number of opioid treatment programs that are federally certified to use methadone and other drugs in treatment, a higher, but still not overwhelming, proportion — just over 63 percent — said they offered screening for hepatitis C.

“We certainly thought the numbers would be higher,” says Asal Sayas, a co-author of the analysis and director of government affairs at amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research. “Testing is one of the most fundamental forms of prevention.”

In primary care settings, the situation sometimes isn’t much better, even when patients have a diagnosed “opioid-use disorder.”

An analysis by Boston Medical Center researchers of nearly 270,000 medical records of people age 13 to 21 who visited federally qualified health centers from 2012 to 2017 found that only 36 percent of the 875 patients with that diagnosis were tested for hepatitis C.

“Even in a setting with an identified risk factor in opioid-use disorder, too few youths are being screened for hepatitis C,” says Dr. Rachel Epstein, a postdoctoral research fellow in infectious diseases at Boston Medical Center and a co-author of the study.

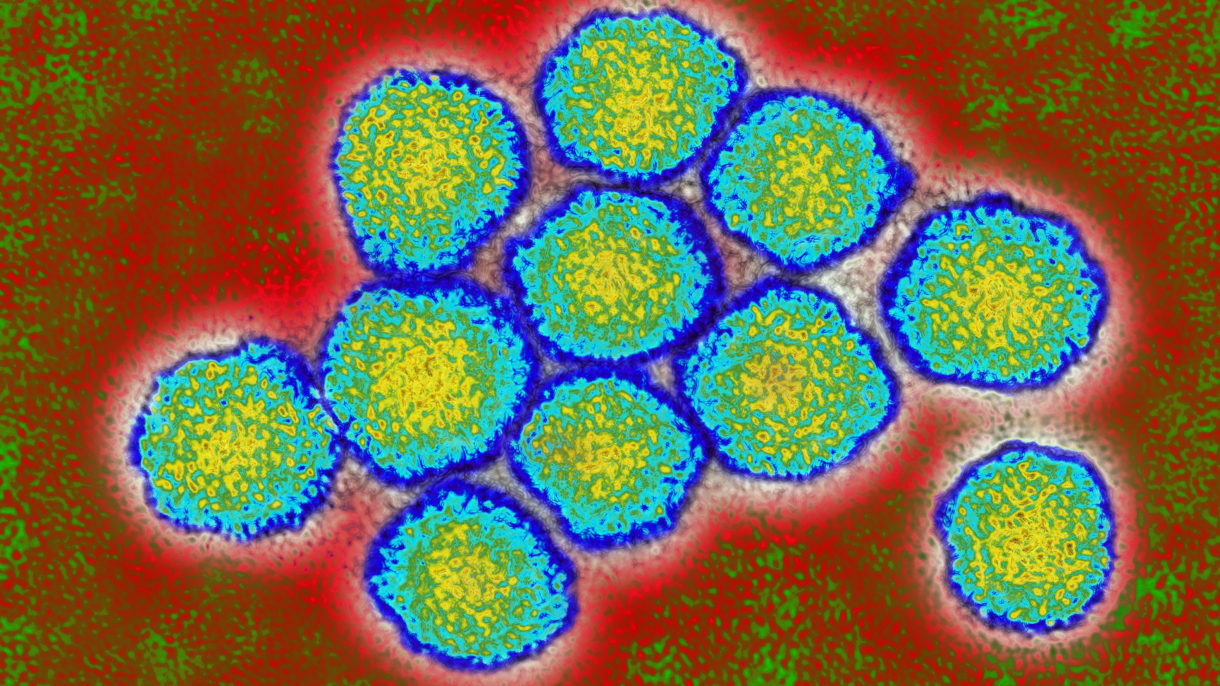

Hepatitis C is a virus that causes inflammation of the liver, in some cases leading to scarring, liver cancer and death. It is transmitted through blood, including contaminated needles that people share when they inject drugs.

The initial test for hepatitis C is an inexpensive blood test to check for antibodies that indicate the person’s been exposed to the virus. If that antibody test is positive, a second test is necessary to find out if the virus is circulating in the bloodstream — that would be a sign of an infection that needs treatment. The second test can cost several hundred dollars, experts say.

To be sure, some federally qualified health centers have made testing for hepatitis C a priority. Clinicians at two community health centers run by Philadelphia Fight — which was established as an AIDS service organization — test many of their patients who are at high risk of having a hepatitis C infection because of their injection-drug use or unsafe sexual practices, such as having sex with an infected partner. Medical personnel get a reminder in the patient’s electronic medical record to do the screenings, often on an annual basis.

“That’s something pretty basic that we’ve done in our community health centers to make sure we’re testing people and providing a cure,” says Dr. Stacey Trooskin, director of viral hepatitis programs at the FIGHT centers and clinical assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine.

Among at least 3.5 million people who have the disease, most are baby boomers who were infected before routine screening of donated blood began in the early 1990s. In recent years, as the opioid epidemic has taken hold, new infections have been concentrated among young people who inject drugs — in particular those between ages 18 and 29, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Complicating the effort to get people screened is the fact that many of the people who enroll in drug treatment programs are uninsured, says Imagine Hope’s Sutton. In states that have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, the program generally picks up the tab for hepatitis C testing and treatment, though often with restrictions.

But 14 states, including Georgia, haven’t expanded that coverage for adults who have incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level ($16,753 for one person).

Insurance coverage isn’t the only challenge. If people have to come back to a clinic for the second test, chances are they may fall through the cracks, and not get that follow-up.

When a patient tests positive, a nurse or counselor at the drug treatment center — who is likely already overtaxed, just working with patients to address their addiction — must also carve out time to explain this new diagnosis and talk through treatment options.

“There’s a whole system of care that needs to be built for these people,” Sutton says, “and, unlike [for] HIV, it doesn’t exist for hepatitis C at this time.”

As with many other clinics around the country, hepatitis C testing at Georgia drug treatment centers is supported with funding from the Focus program, sponsored by drugmaker Gilead; it was the first company to offer a new class of highly effective drugs that generally cure hepatitis C in three months or less with few side effects.

Finding resources to pay for treatment is also difficult. The high costs of the new drugs when they were introduced led some public and private insurers to strictly limit access. But, in recent years, drug prices have come down as more drugs hit the market and many states have loosened Medicaid restrictions.

For example, New Mexico’s Medicaid program doesn’t require that people be sick or abstain from using illicit drugs or alcohol for a time before starting treatment.

Still, “hepatitis C testing remains out of reach for many because their providers aren’t aware that their patients can get treated,” says Kimberly Page, an epidemiologist and professor of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico, who focuses her study on hepatitis C.

Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit news service, is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation and not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))