The Trump administration is now warning about “fake families” amid the surge of Central American migrants crossing the southern border. Border agents have noticed an uptick in adult immigrants traveling with minors who are not their children. The administration suspects foul play, but immigrant advocates say they’re just trying to make it into the U.S. for a better life.

“Cases of fake families are cropping up everywhere and children are being used as pawns,” Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen told a congressional committee last week. “In fact, we have even uncovered child recycling rings, a process in which innocent children are used multiple times to help migrants gain illegal entry.”

$1,500 per child, 13 times

Nielsen singled out one particularly sordid case involving a Guatemalan woman living in Charleston, S.C. Officials say the woman paired immigrant children with adults who are not their parents. They would present themselves at the border knowing that families traveling together are likely to be released to live in the U.S. until they get to immigration court.

Adult immigrants who travel alone are usually detained or quickly deported. Local offices of Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the U.S. attorney declined to provide details about the case.

Border Patrol Associate Intelligence Chief Carl McClafferty described the South Carolina case in an appearance with Nielsen and the president in February at the White House.

“One of the indictments was a woman who was being paid $1,500 a child to take the children back to Guatemala who are not part of the actual family unit,” he said. “She tried to do this 13 times.”

Fraudulent family units

Child recycling cases are rare. What is a growing problem are fake documents. Up and down the southwest border, federal agents are seeing them. In the Yuma, Ariz., sector alone, they’ve had 450 instances of “fraudulent family units” since October, according to a local spokesman.

In El Paso, Texas, Border Patrol Special Operations Supervisor Ramiro Cordero has noticed it, too. “We found cases where adults have been coming in with kids who are not their kids, yet they’re claiming that they’re their children. We found birth certificates that have been forged,” Cordero says.

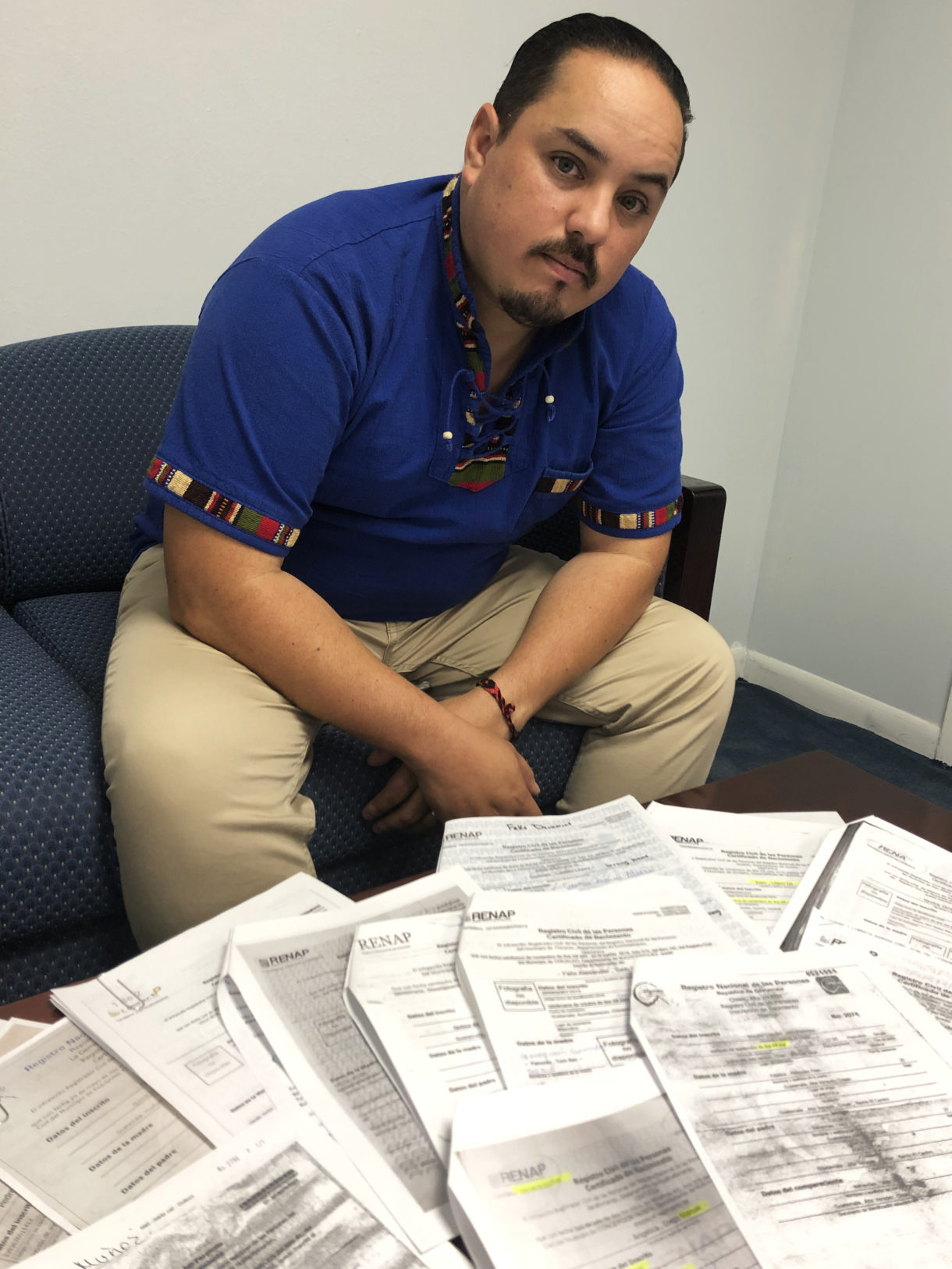

When agents in El Paso suspect something fishy, they send the questionable birth certificates to the Guatemalan consul in the city of Del Rio. Officials there check the document’s authenticity with the database of the Guatemalan National Persons Registry.

Guatemalan Consul Tekandi Paniagua says he’s not aware of any recycled children. “Unfortunately,” he says, “the consulate has detected lots of fake identity documents in recent months.”

Paniagua says that in most of the cases they’ve looked into, the pair involves an adult neighbor or relative who is not the parent, and a child is willfully traveling with them. In many cases, he says, immigrant parents already in the United States pay for fake documents for an adult traveling companion to bring their children.

The consul says the price for fake documents ranges from $200 to $700. He called it “an additional service provided by organizations that work for human smugglers.”

In some cases, it’s a bogus document with the wrong watermark, wrong stamp and wrong agency logo. In other cases, the document is authentic, but a name or an age has been changed. The consulate staff has also come across cases where a young adult altered their birth date to under 18 so they could go to a federally contracted youth shelter where conditions are more benign than adult detention.

Human smuggling or human trafficking?

Even before they see the documents, federal agents say when they encounter some immigrant families they can tell something is not right.

“A young man has arrived with a small child. He had no diapers, no bottle, nothing. He did not even know how to feed the child,” says Monica Mapel, assistant agent in charge of Homeland Security Investigations in San Antonio. “So that tells me that’s not your child. You’re not a father who’s been caring for that child.”

Mapel has begun to explore whether faux family schemes are mostly a matter of illegal immigration or child exploitation.

“Is it continuation of human smuggling? Or is it worse — human trafficking? As an investigator my mind is wide open,” Mapel says.

In the current historic immigrant surge, officials in El Paso have apprehended as many as 1,000 family members a day. A majority come from Guatemala. Paniagua says the consulate is discovering about a dozen sham birth certificates every day. They’re concerned, but not alarmed.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))