The powerful gene-editing technique called CRISPR has been in the news a lot. And not all the news has been good: A Chinese scientist stunned the world last year when he announced he had used CRISPR to create genetically modified babies.

But scientists have long hoped CRISPR — a technology that allows scientists to make very precise modifications to DNA — could eventually help cure many diseases. And now scientists are taking tangible first steps to make that dream a reality.

For example, NPR has learned that a U.S. CRISPR study that had been approved for cancer at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia has finally started. A university spokesman on Monday confirmed for the first time that two patients had been treated using CRISPR.

One patient had multiple myeloma, and one had sarcoma. Both had relapsed after undergoing standard treatment.

The revelation comes as several other human trials of CRISPR are starting or are set to start in the U.S., Canada and Europe to test CRISPR’s efficacy in treating various diseases.

“2019 is the year when the training wheels come off and the world gets to see what CRISPR can really do for the world in the most positive sense,” says Fyodor Urnov, a gene-editing scientist at the Altius Institute for Biomedical Sciences in Seattle and the University of California, Berkeley.

Here are highlights of the year ahead in CRISPR research, and answers to common questions about the technology.

What is CRISPR exactly?

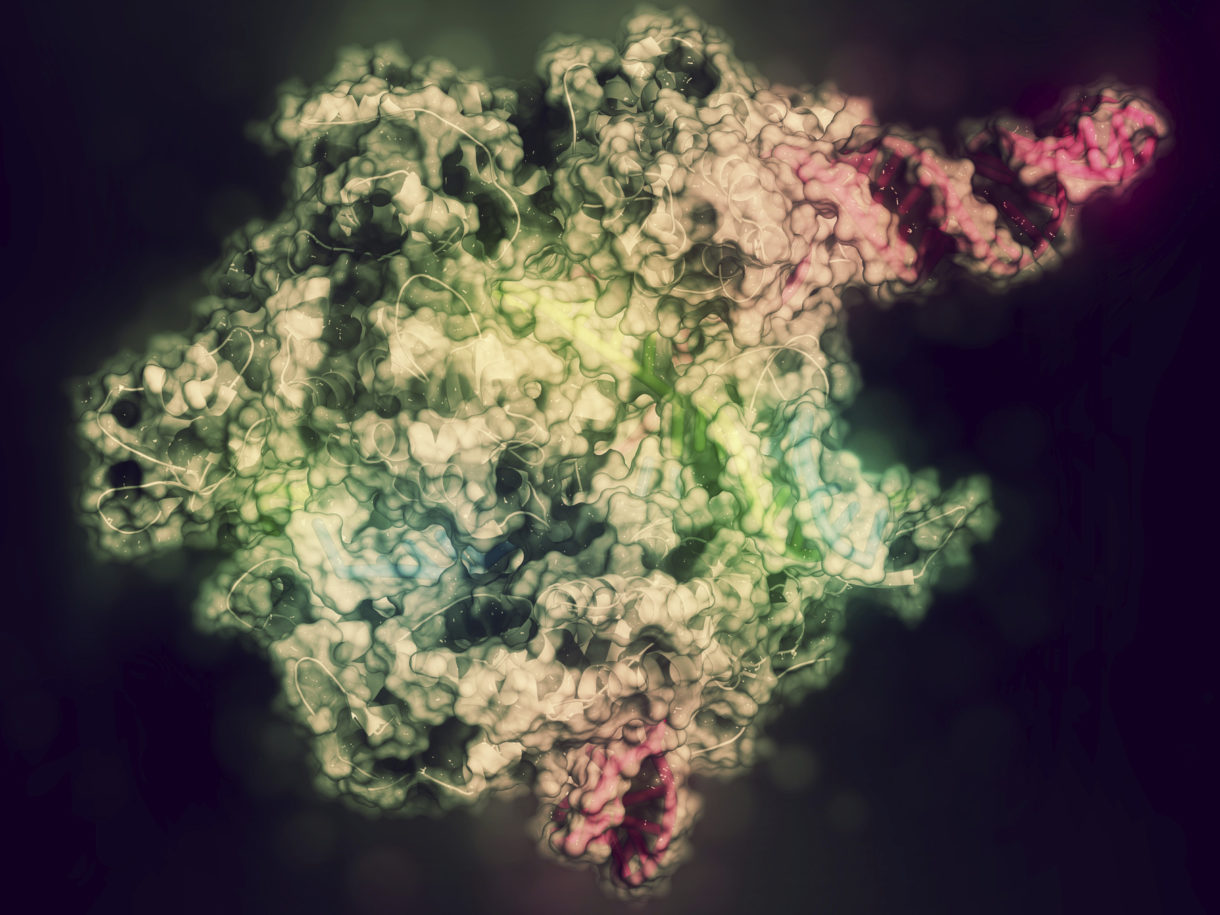

CRISPR is a new kind of genetic engineering that gives scientists the power to edit DNA much more easily than ever. Researchers think CRISPR could revolutionize how they prevent and treat many diseases. CRISPR could, for example, enable scientists to repair genetic defects or use genetically modified human cells as therapies.

Traditional gene therapy uses viruses to insert new genes into cells to try to treat diseases. CRISPR treatments largely avoid the use of viruses, which have caused some safety problems in the past. Instead they directly make changes in the DNA, using targeted molecular tools. The technique has been compared to the cut and paste function in a word processing program — it allows scientists to remove or modify specific genes causing a problem.

Is this the same technique that caused a recent scandal when a scientist in China edited the genes of two human embryos?

There’s an important difference between the medical studies under discussion here and what the Chinese scientist, He Jiankui, did. He used CRISPR to edit genes in human embryos. That means the changes he made would be passed down for generations to come. And he did it before most scientists think it was safe to try. In fact, there have been calls for a moratorium on gene-editing of heritable traits.

For medical treatments, modifications are only being made in the DNA of individual patients. So this gene-editing doesn’t raise dystopian fears about re-engineering the human race. And there’s been a lot of careful preparation for these studies to avoid unintended consequences.

So what’s happening now with new or planned trials?

We’ve finally reached the moment when CRISPR is moving out of the lab and into the clinic around the world.

Until now, only a relatively small number of studies have tried to use CRISPR to treat disease. And almost all of those studies have been in China, and have been aimed at treating various forms of cancer.

There’s now a clinical trial underway at the University of Pennsylvania using CRISPR for cancer treatment. It involves removing immune system cells from patients, genetically modifying them in the lab and infusing the modified cells back into the body.

The hope is the modified cells will target and destroy cancer cells. No other information has been released about how well it might be working. The study was approved to eventually treat 18 patients.

“Findings from this research study will be shared at an appropriate time via medical meeting presentation or peer-reviewed publication,” a university spokesperson wrote in an email to NPR.

But beyond the cancer study, researchers in Europe, the United States and Canada are launching at least half a dozen carefully designed studies aimed at using CRISPR to treat a variety of diseases.

What other diseases are they testing treatments for?

Two trials sponsored by CRISPR Therapeutics of Cambridge, Mass., and Vertex Pharmaceuticals of Boston are designed to treat genetic blood disorders. One is for sickle cell disease, and another is a similar genetic condition called beta thalassemia.

In fact, the first beta thalassemia patient was recently treated in Germany. More patients may soon get their blood cells edited using CRISPR at that hospital and a second clinic in Germany, followed by patients at medical centers in Toronto, London and possibly elsewhere.

The first sickle disease patients could soon start getting the DNA in their blood cells edited in this country in Nashville, Tenn., San Antonio and New York.

And yet another study, sponsored by Editas Medicine of Cambridge, Mass., will try to treat an inherited form of blindness known as Leber congenital amaurosis.

That study is noteworthy because it would be the first time scientists try using CRISPR to edit genes while they are inside the human body. The other studies involve removing cells from patients, editing the DNA in those cells in the lab and then infusing the modified cells back into patients’ bodies.

Finally, several more U.S. cancer studies may also start this year in Texas, New York and elsewhere to try to treat tumors by genetically modifying immune system cells.

What can go wrong with CRISPR? Are there any concerns?

Whenever scientists try something new and powerful, it always raises fears that something could go wrong. The early days of gene therapy were scarred by major setbacks, such as the case of Jesse Gelsinger, who died after an adverse reaction to a treatment.

The big concern about CRISPR is that the editing could go awry, causing unintended changes in DNA that could cause health problems.

There’s also some concern about this new wave of studies because they are the first to get approved without going through an extra layer of scrutiny by the National Institutes of Health. That occurred because the NIH and FDA changed their policy, saying only some studies would require that extra layer of review.

“Every human on the planet should hope that this technology works. But it might work. It might not. It’s unknown,” says Laurie Zoloth, a bioethicist at the University of Chicago. “This is an experiment. So you do need exquisite layers of care. And you need to really think in advance with a careful ethical review how you do this sort of work.”

The researchers conducting the studies say they have conducted careful preliminary research, and their studies have gone through extensive scientific and ethical review.

When might we know whether any of these experimental CRISPR treatments are working?

All of these studies are very preliminary and are primarily aimed at first testing whether this is safe. That said, they are also looking for clues to whether they might be helping patients. So there could be at least a hint about that later this year. But it will be many years before any CRISPR treatment could become widely available.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))