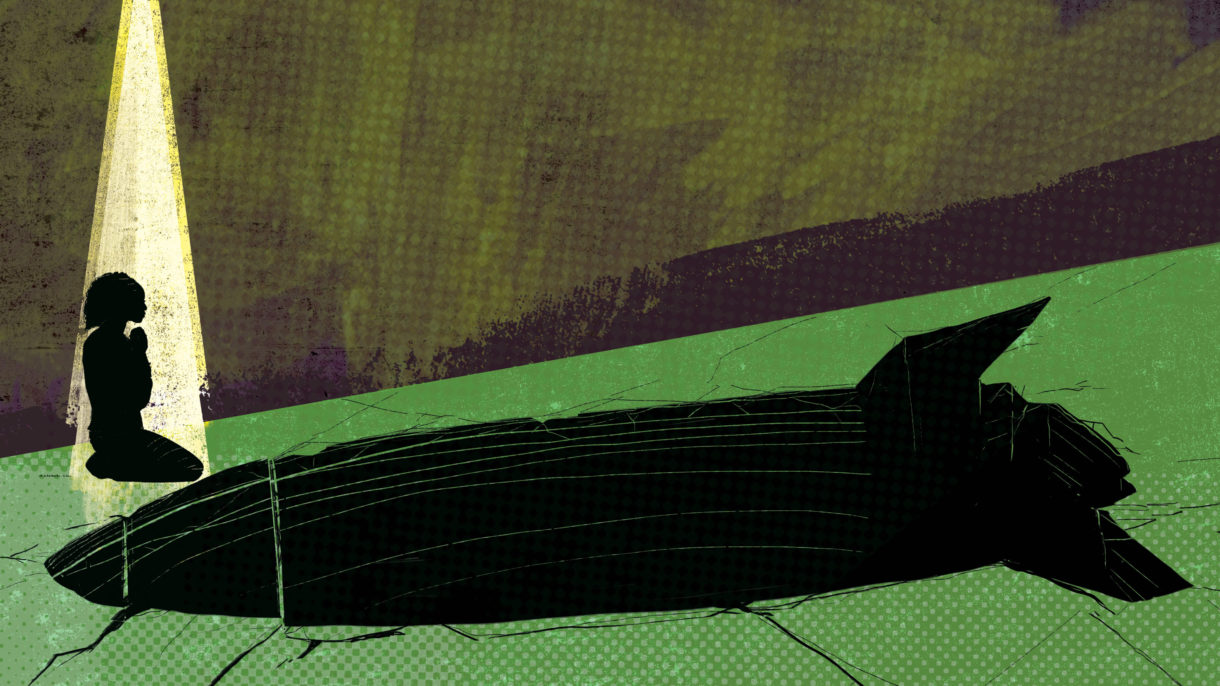

What’s the link between war and religion? Does living through the traumas of conflict make people more religious – or turn them against religion?

Those age-old questions are probed in two studies.

“War Increases Religiosity” appears in Nature: Human Behavior. A team led by Joseph Henrich, chairman of the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology of Harvard University, analyzed interview responses from 1,709 individuals in 71 villages in three countries that had suffered prolonged, brutal internal conflicts that did not revolve around religious or ethnic differences: Sierra Leone’s civil war, 1991-2002; the Lord’s Resistance Army insurgency in Uganda, 1986-2006; and Tajikistan’s civil war and continuing political violence.

The data showed that people who had been more intensely affected by the violence of war were more likely to join or participate in religious groups and practice religious rituals. The data, collected in 2010 and 2011, came from previously published work by other researchers.

The more profound the impact of war on an individual — such as the death, injury or abduction of a household member — the greater the likelihood grew of that person turning to religion. By contrast, those who had been less affected by the impact of war were also less likely to join a a religious group. The statistical breakdown showed that for those in Sierra Leone, greater exposure to war made it 12% more likely individuals would turn to religion; 14% more for those in Uganda; and 41% more for Tajikstan.

Even as years passed, Henrich’s latest study found that religious practice continued to play a significant role in the lives of many of those surveyed. “These effects on religiosity persist even 5, 8 and 13 years post-conflict,” according to the study. The effects held true whether those surveyed were Muslim or Christian.

So what does that mean in terms of day-to-day behavior? In Henrich’s previous work, he had found that religion led people to be more “prosocial” — that is, more supportive, cooperative and generous — but in a particular way. “When people hear the word cooperation, they interpret that positively,” he said. But his study showed a “more narrow” type of cooperation that only included people in one’s own group or village while excluding outsiders. As Henrich put it, “When I’m hit by a shock, what should I do? Who should I turn to? The groups you’re already in become tighter, and you’re less interested in reaching out to those who are not” in your in-group.

The positive side is that such cooperation could lead to nation building. But the danger, Henrich says, is that these ingredients can alternatively lead to what he calls a “negative feedback loop.” In that scenario, these already tightly knit religious groups could, in the event of an attack or if they fear one is imminent, band together to fight off other groups and defend their own religious beliefs.

And that’s the mixed message from the study’s findings. Even though the groups studied by Henrich and his colleagues had not initially experienced a war with a religious element baked in, they could have a religious awakening in the aftermath that could foster “parochial cooperation” – but could also “catalyze ongoing cycles of violent conflict.”

Henrich echoes the conclusions of an earlier research study, published in 2016, by psychology professors Hongfei Du of Guangzhou University and Peilian Chi of the University of Macau. They also found that the greater exposure to war, the more likely people are to become more religious, belong to religious groups and participate in religious rituals. That was their takeaway after analyzing responses from 82,772 individuals in 57 countries contained in the 2010 World Values Survey.

In a post-war environment, religion can serve as a psychological buffer against worry about future conflicts, they write — and can also help people achieve a strong sense of belonging to a group.

And yet, Du wrote in his email to NPR, some research has shown that a different factor could tip the cycle toward peacemaking instead: whether the religious leaders hold and emphasize compassionate values rather than promote violent solutions to conflicts. It’s an idea that was crystallized in a quote from Gandhi: “The need of the moment is not one religion, but mutual respect and tolerance of the devotees of the different religions.”

Diane Cole writes for many publications, including The Wall Street Journal and The Jewish Week, and is book columnist for The Psychotherapy Networker. She is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges. Her website is dianejcole.com.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))