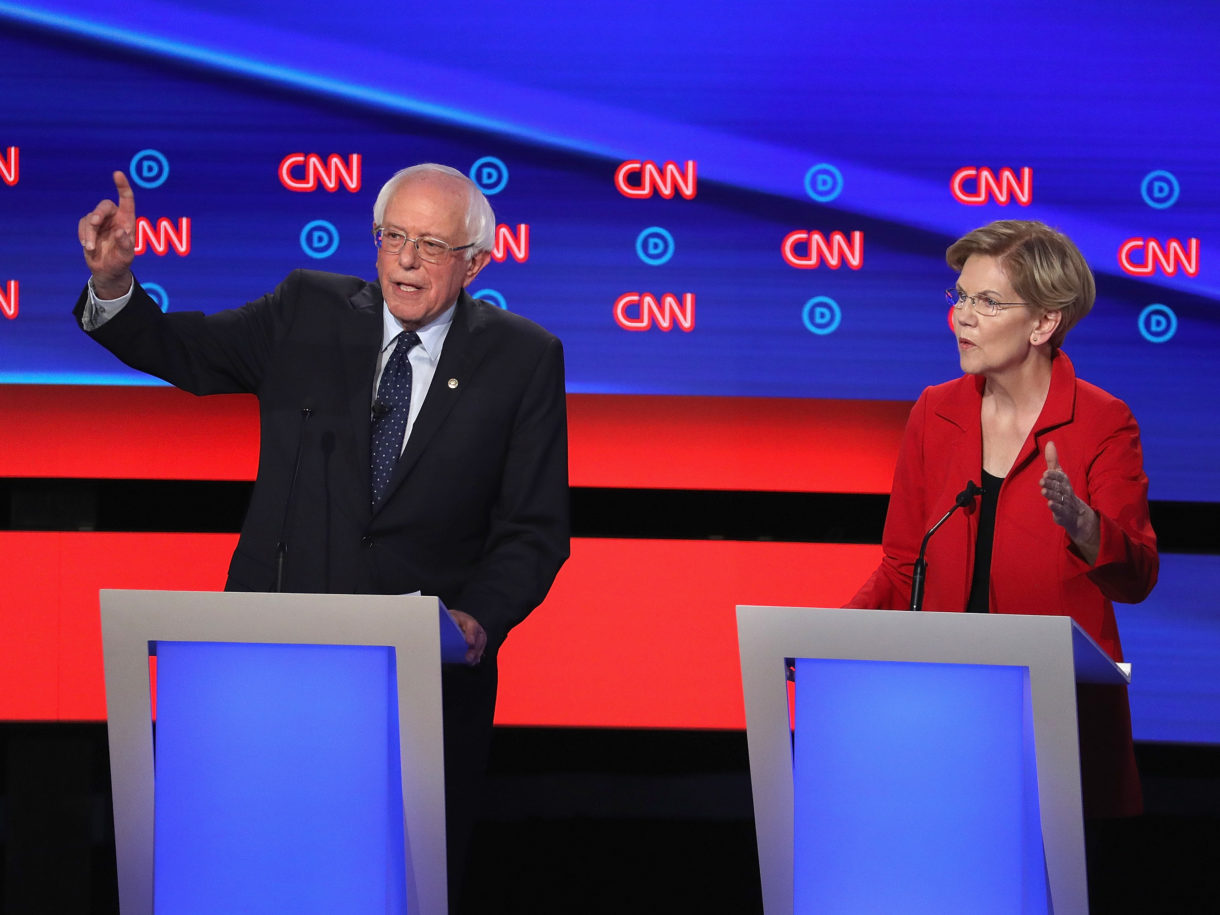

At the Democratic debate tonight, one particular aspect of Bernie Sanders’ “Medicare for All” plan got special scrutiny.

After a back-and-forth over how to pay for the plan, CNN moderator Jake Tapper pointedly asked Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who has sponsored Sanders’ plan: “Would you raise taxes on the middle class to pay for Medicare for All — offset, obviously, by the elimination of insurance premiums — yes or no?”

“Costs will go up for billionaires and go up for corporations,” Warren said. “For middle-class families, costs — total costs — will go down.”

This exchange encapsulated one of the biggest arguments in tonight’s debate over health care: whether candidates would raise taxes, and whether families’ total health care bills would go up.

Tapper went on to ask other candidates to weigh in on the same question on taxes. Sanders envisions that those taxes would be replacing other health spending. The broader question here is how much people would end up spending in total on health care.

The answer to that is hard to determine. The bill as laid out right now isn’t very specific on how revenues would be raised, as the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Larry Levitt told NPR.

“What would happen to the middle class depends entirely on the details. Under the current Medicare for All proposals, middle-class people would have no premiums, deductibles or copays, and save a lot of money on health care,” he said. “Whether they would pay more or less on net would depend on which taxes go up to pay for the plan.”

When Sanders released his latest Medicare for All bill, he released a document called “options to finance Medicare for All” — a list of ways to potentially pay for parts of the bill.

One potential tax Sanders listed that has been particularly controversial is a 4% “income-based premium” that households making more than $29,000 per year would pay. He also calls for taxes on employers and greater taxes on high-income households.

Sanders argues that while, yes, his plan may end up taxing middle-class households more, the fact that they would no longer be paying premiums and copays would more than make up for whatever they might end up paying in taxes.

If that 4% tax were imposed, it is indeed possible that some families could end up paying less. But that depends, for example, on the family and how much they spend on health care now.

Not only that, but all of this depends on how much Sanders’ plan costs and whether these taxes really would cover the entire cost of the plan. One 2016 report from the Urban Institute found that taxes proposed by Sanders wouldn’t fully cover his Medicare for All plan at the time.

That study also raised the question of knock-on effects of taxes on employers: on the one hand, the study pointed out, not paying premiums anymore could mean more compensation for some workers. On the other hand, new payroll taxes could mean reduced wages at some businesses.

This debate over middle-class taxes is not particular to Sanders and Warren; Kamala Harris’ new health plan, which she calls her version of Medicare for All, got attention this week in part because of her promise not to raise taxes for the “middle class.” In her plan, she said she would impose new taxes on families earning more than $100,000.

Joe Biden swung back at that — his deputy campaign manager, Kate Bedingfield, in a statement said that Harris’ plan represented “a refusal to be straight with the American middle class,” adding that they believed her plan would mean middle-class tax hikes.

All of which is to say that this fight over middle-class taxes and health care overhauls could easily continue in Wednesday night’s debate.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))