Shannon Wood Rothenberg walked into her annual physical feeling fine. But more than a year later, she’s still paying the price.

Routine bloodwork from that spring 2018 medical visit suggested iron-deficiency anemia. The condition runs in Rothenberg’s family and is often treated with over-the-counter iron pills, which typically cost under $10 for a month’s supply. Her doctor advised exactly that.

But after two months with no change, the doctor told Rothenberg to see a hematologist who could delve into the source of her problem and infuse an iron solution directly into her veins.

So, the 48-year-old public school teacher went twice in July 2018 to a cancer center, operated by Saint Joseph Hospital in Denver, to get infusions of Injectafer, an iron solution.

When the bill arrived in March, after prolonged negotiations between the hospital and her insurer, Rothenberg and her husband were floored.

The hospital initially had billed more than $14,000 per vial of Injectafer. Since her treatment was in network, Rothenberg’s insurance plan negotiated a much cheaper rate: about $1,600 per vial. She received two vials. Insurance paid a portion, but Rothenberg still owed the hospital $2,733, based on what was still unpaid in her family’s $9,000 deductible.

“I have twins who are going to college next year. I’m already a bit freaked out about upcoming expenses,” she says. “I don’t have $2,700 sitting around.”

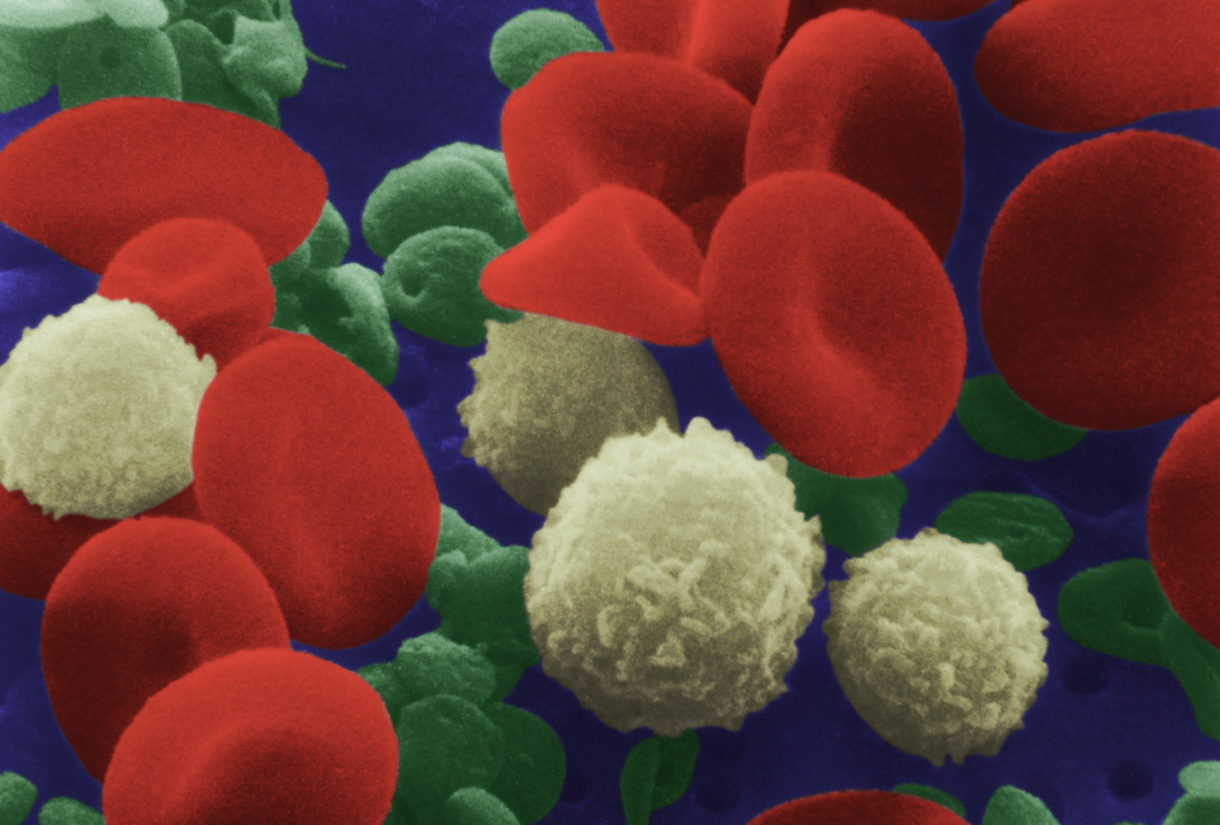

Anemia, the principal outgrowth of low iron levels, can cause headache, fatigue and an irregular heartbeat. People with certain medical conditions, including a history of heavy menstrual periods, inflammatory bowel disease and kidney failure, among others, are prone to low iron levels and anemia, which can be severe.

Crunching the national data

Although Rothenberg had private health insurance, a close look at Medicare data suggests her experience with pricey iron infusions is pretty common. Since 2013, the first year for which data are available, about 9 million Americans in the federal government’s health plan for people 65 and above have gotten iron infusions each year. That’s almost one infusion for every five Medicare recipients.

In other countries, doctors usually would not be so quick to resort to iron infusions for anemia — especially in healthy patients like Rothenberg, who have no underlying disease and no obvious symptoms.

In Great Britain, for example, it would be extremely unlikely that IV iron would be administered,” says Richard Pollock, a health economist at London-based Covalence Research, who studies the use of iron products.

But one key difference between the United States and other countries is that American physicians and hospitals can profit handsomely from infusions. Under Medicare, a doctor’s payment is partly based on the average sales price of the prescribed drug. Critics say that gives health practitioners an incentive to pick the newer, more expensive option.

For patients who have private insurance, hospitals and doctors can mark up prices even more. Intravenous infusions, generally administered in a hospital or clinic, also generate a “facility fee.”

That creates a financial incentive to favor the most expensive infused treatments, rather than pills or simple skin injections that patients can use readily at home.

Indeed, a Kaiser Health News analysis of Medicare claims found that Injectafer and Feraheme — the two newest (and priciest) infusions on the American market — made up more than half of IV iron infusions in 2017, up from less than a third in 2014. Cheaper, older formulations — which can go for as little as a tenth the cost — have seen their share of Medicare claims fall dramatically.

Situations like these, which drive up Medicare spending, are why the Trump administration has suggested changing how Medicare pays for intravenous drugs. The administration would tie Medicare reimbursements for some IV drugs to the price paid in countries that set drug prices at a national level — prices that are partly based on an estimate of each drug’s comparative value. This plan has generated sharp backlash from conservative lawmakers and the medical and pharmaceutical industries.

Physicians argue that they simply prescribe the most effective medication for patients, regardless of what the payment system would suggest.

But the government’s own Medicare claims data, research and stories like Rothenberg’s paint a different picture.

“When there’s a financial incentive … that might move the physician away from the choice the patient would optimally make, we might be concerned,” says Aditi Sen, a health economist at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who is researching how doctors prescribe and are paid for intravenous iron treatments.

The example of iron infusions, she adds, suggests “a clear financial incentive to prescribe more expensive drugs.”

“Iron-poor tired blood” and the marketing of iron supplements

Treatments for iron deficiency are nearly 100 years old. Geritol, a decades-old dietary iron supplement for “iron-poor tired blood,” was among the first medicines widely advertised on TV in the 1950s and ’60s.

The first federally approved iron infusion didn’t hit the U.S. market until 2000, but the treatments have since surged in popularity. For one thing, infusions carry fewer side effects than do pills, which can cause constipation or nausea. And scientific advances have mitigated the risks of intravenous iron, although getting infusions still comes with inconvenience, some discomfort, the risk of infection at the IV site and, rarely, serious allergic reactions.

Five branded products now dominate the American market for IV iron, and three have generic counterparts. They have different chemical formulations, but, by and large, are considered mostly medically interchangeable.

“There’s not a huge amount of difference in the efficacy of iron formulations,” Pollock says. So, for value, “the question really does come down to cost.”

Doctors are supposed to recommend infusions only if patients don’t respond to iron pills or dietary changes, Pollock says. Instead of steering patients toward “unnecessarily costly” infusions, physicians should determine the underlying cause of low iron and treat that directly.

Injectafer, which Rothenberg received, is one of the most expensive infusions, retailing for more than $1,000 a vial. And, as Rothenberg learned the hard way, hospitals can charge privately insured patients whatever they choose. Insurers then negotiate that hospital “list price” down.

An analysis of private insurance claims conducted by the Health Care Cost Institute, an independent research group funded by insurers, found that in 2017, private health plans paid $4,316 per visit, on average, if a patient received Injectafer infusions. Feraheme, the next most expensive infusion drug, cost private plans $3,087 per visit, while the other three on the market were considerably cheaper. Infed was $1,502, Venofer $825 and Ferrlecit $412, the institute found, in an analysis for Kaiser Health News.

The share of newer, pricier infusions has crept up in the private market too. In 2017, 23% of privately billed iron infusion visits involved Injectafer or Feraheme, compared with 13% in 2015, according to the institute’s data.

Nobody told Rothenberg cheaper options might exist or warned her about her treatment’s price, she says. The hematologist who treated her did not respond directly to our repeated requests for comment.

But Alan Miller, the chief medical director of oncology for SCL Health (Saint Joseph’s umbrella organization), says the hospital stopped using Injectafer in August 2018 — a month after Rothenberg’s visit — because of the relatively high cost to patients. The hospital now turns to Venofer and Feraheme, instead.

There are some other, nonmedical reasons doctors might choose the more expensive drug. Newer, more expensive drugs are more likely to be heavily marketed directly to doctors, says Stacie Dusetzina, an associate professor of health policy at Vanderbilt University.

Walid Gellad, an associate health policy professor at the University of Pittsburgh, says some formulations may be more convenient in terms of how many doses they require or how long patients have to sit for an infusion. Or a certain patient might have a distinctive profile that makes one drug an obviously better fit.

None of those explanations sit particularly well with Rothenberg, whose iron levels are now fine — but who is still paying off her $2,700 bill in installments over two years.

“If they had said, ‘This is going to cost you $3,000,’ I would have said, ‘Oh, never mind,’ ” Rothenberg now says. “It’s a big mental shift for me to say, ‘I’m supposed to weigh the costs against the health benefits. I’m not supposed to necessarily do what the doctor says.’ ”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation and is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))