Timothy C. Winegard’s The Mosquito is as wildly entertaining as any epic narrative out there. It’s also all true.

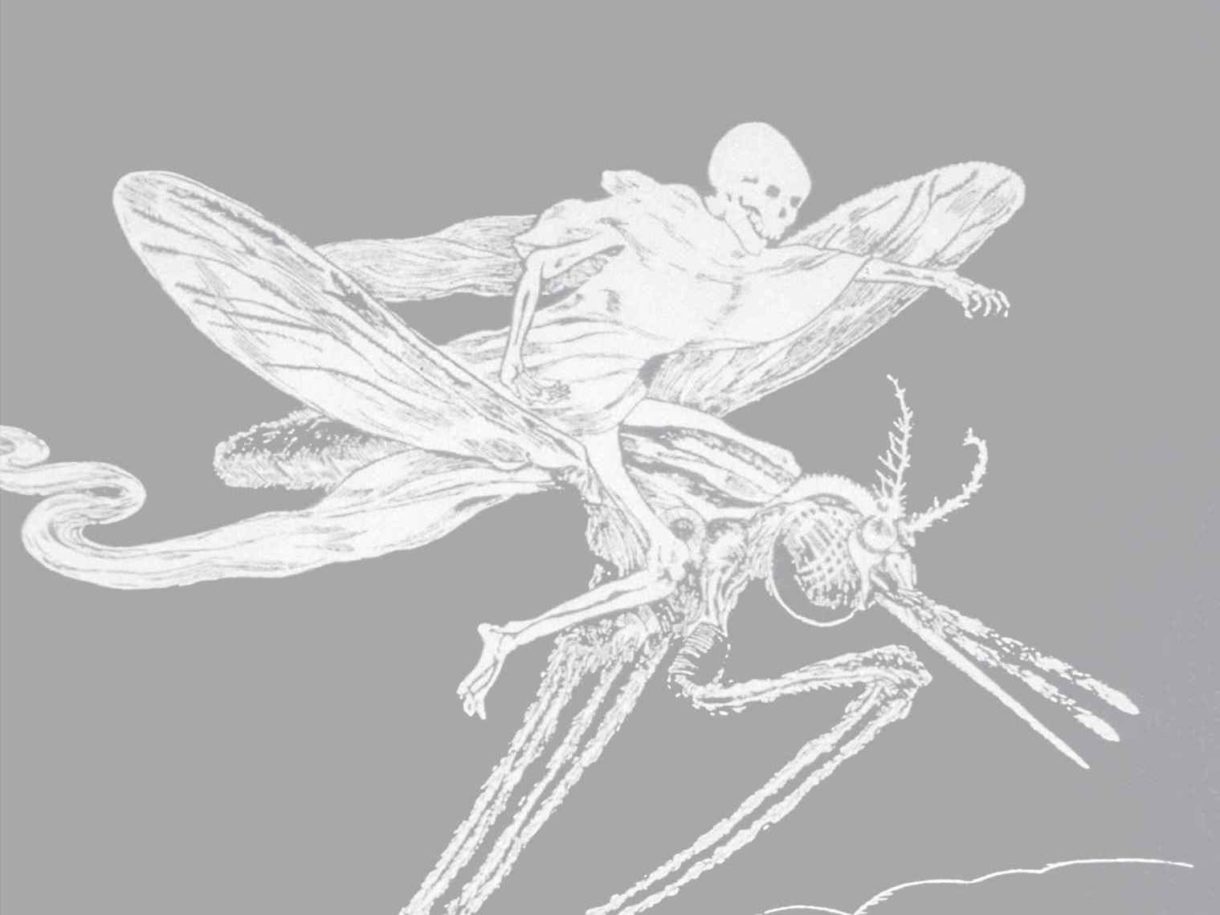

The book starts with a couple of revelations: Mosquitoes played a role in the extinction of dinosaurs — and the diseases they carry have been around for so long and with such force that they have managed to alter human DNA. But that’s just the start. According to Winegard, the mosquito “has ruled the earth for 190 million years and has killed with unremitting potency for most of her unrivaled reign of terror.” How much killing? He notes an estimate of 52 billion people, which is more than all wars in history combined.

The Mosquito is an extremely well-researched work of narrative nonfiction that tells the story of the world through the lens of the role that mosquitoes and mosquito-borne illnesses have played in it. Wars, conquests, migration, slavery, economies and medicine have all been shaped by the mosquito. As Winegard states, “General Anopheles,” as he refers to the insect by a genus name, has “razed armies and decided the outcome of countless course-altering wars.” Humans have been affected by the mosquito for as long as Homo sapiens has walked the Earth, and the small flying insect has adapted to every advance that humanity has made to rid itself of the diseases that the insect carries, which include malaria, encephalitis, yellow fever, dengue, Zika, West Nile virus, chikungunya and other maladies. These adaptations have helped the insect retain its throne as the deadliest animal on the planet:

“While the mosquito is miraculously adaptable, it is also a purely narcissistic creature. Unlike other insects, it does not pollinate plants in any meaningful way or aerate the soil, nor does it ingest waste. Contrary to popular belief, the mosquito does not even serve as an indispensable food source for any other animal. She has no purpose other than to propagate her species and perhaps kill humans. As the apex predator throughout our odyssey, it appears that her role in our relationship is to act as a countermeasure against uncontrolled human population growth.”

The Mosquito starts in antiquity (the first time the insect was written about was in 3200 BC), but the real rich history starts in Athens, Greece. From there the narrative works its way through human history and covers in detail the rise of the Roman Empire, the Crusades, the birth and collapse of the Mongol Empire (Genghis Khan was unstoppable — until a mosquito showed up), the Columbian Exchange and the birth of the Americas (during which mosquitoes became one of the primary driving forces behind slavery) and the birth and history of the United States all the way up to the Civil War. It ends in modern times, with the role mosquitoes now play in various countries around the world. The writing is engaging, and Winegard masterfully weaves historical facts and science to offer a shocking, informative narrative that shows how who we are today is directly linked to the mosquito:

“For Rome, the mosquito ultimately proved to be a double-edged sword. Initially, she safeguarded Rome from the military genius of Hannibal and his conquering Carthaginians, encouraging and emboldening the construction of empire and the widespread dissemination of Roman cultural, scientific, political, and academic advancements, securing the enduring legacy of the Roman era. Over time, however, while she continued to defend Rome against foreign plunderers, including the Visigoths, Huns, and Vandals, from her headquarters in the Pontine Marshes, she was also busy piercing the heart of Rome itself.”

Winegard uses countless historical texts, books, biographies, medical books and even the works of novelists, playwrights and poets (malaria shows up in eight of Shakespeare’s plays) to enrich his narrative. The result is an outstanding book that reshapes our past under a new lens — and helps explain some baffling events. For example, he explains how “Hernan Cortes did not conquer six million Aztecs, just as Francisco Pizarro did not subjugate ten million Inca. Following crippling epidemics of smallpox and endemic malarial fever, these two conquistadors simply rounded up the few ailing survivors and sold them into slavery.”

From exploring the notion that any attempt by Europeans to penetrate Africa in search of gold and resources was met by “an impenetrable perimeter of lethal mosquito defenders” to author Dr. Seuss’ famous campaign for DDT, Winegard takes readers on a truly immersive ride through the tumultuous relationship between humans and mosquitoes, which ends in modern history, where the mosquito has evolved and become immune to many insecticides.

On page 1 of The Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator, Winegard declares: “We are at war with the mosquito.” Some 436 pages later, after exploring the role the insect has played in shaping our world, the author makes a chilling declaration: “We are still at war with the mosquito.” Yes, it’s somber, but this book illuminates what we’re dealing with — and suggests what we might do differently to keep our most lethal predator under control.

Gabino Iglesias is an author, book reviewer and professor living in Austin, Texas. Find him on Twitter: @Gabino_Iglesias.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))