Splat! A lucky strike and the telltale red splodge that your nightly tormentor has sucked its last blood vessel.

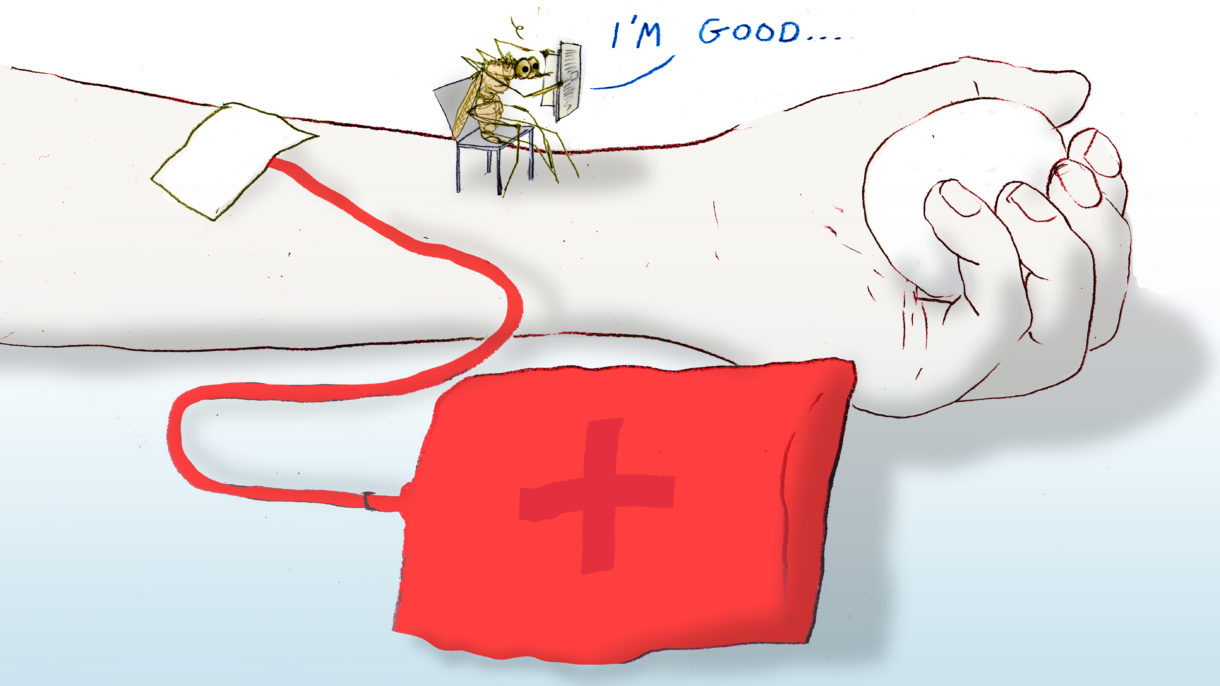

Staring at the mess on the wall, you might find it hard to believe that so small an insect can carry so much blood. But female mosquitoes have a knack for eating, doubling their body weight with each meal.

“They can barely fly,” laughs Leslie Vosshall, a neurobiologist at Rockefeller University, who’s hoping to control mosquitoes, as well as the diseases they carry, by switching off their enormous appetite.

In a paper published Thursday in the journal Cell, Vosshall and her team demonstrate how human diet drugs satiate mosquitoes’ bloodlust for several days — so they are less likely to feed on humans and spread diseases and will also produce fewer offspring.

“When they’re hungry, these mosquitoes are super motivated. They fly toward the scent of a human the same way that we might approach a chocolate cake,” Vosshall says. “But after they were given the drug, they lost interest.”

The method taps into female mosquitoes’ natural gluttony. Each supersize meal provides enough nutrients to support the typical clutch of around 100 eggs. After she has eaten, the mosquito loses her appetite for at least four days while her eggs develop.

But as soon as a mosquito lays her eggs in a pool of stagnant water, she is off again in search of a mate and a meal. A female mosquito can breed several times in her lifetime of six to eight weeks, and in the process she can bite many people — which makes her a reliable vessel for spreading diseases.

Vosshall and her team set out to identify and manipulate the hormone pathways responsible for this behavior. Because similar pathways for hunger are found in many animals — that is, they have similar evolutionary roots — she started with off-the-shelf human diet drugs.

“On a lark we thought, ‘Let’s go for it. Let’s do the craziest experiment possible and get some human diet drugs and see if they work on mosquitoes,’ ” Vosshall told NPR.

“It was surprising that it worked so well.”

In a series of lab experiments, Aedes aegypti mosquitoes (which spread dengue fever, yellow fever and Zika virus) were fed these diet drugs by mixing them into a chemical solution that also contained ATP — a molecule found inside most animal cells that mosquitoes find irresistible. The diet drugs came in powder form. For several days after drinking this solution, the mosquitoes showed little interest when offered the bare arms of human volunteers. Even the smell of dirty nylon stockings, saturated with human scent, was not enough to tempt them.

After testing human diet drugs, the team homed in on the specific receptors that these drugs activate inside the mosquito brain. Then they could search through a general catalog of more than 265,000 chemicals to find a new suite of drugs that also activate this receptor — but that control only the appetite of mosquitoes and similar biting insects.

“Human drugs are owned by pharmaceutical companies, and so we wanted to find something where the intellectual property wasn’t locked up. That’s important in [developing countries] for deployment,” Vosshall explains. And for obvious reasons, widely releasing human diet drugs into the environment is not a good idea.

In recent years, scientists have developed an advanced arsenal of tools in the war against mosquitoes — from potent new insecticides to gene drives and bacterial infection. But rarely have they tried to control mosquitoes’ behavior.

“There is a real need for novel approaches to controlling insects that transmit diseases,” says James Logan of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, who was not involved in the study.

According to the World Health Organization, mosquito-borne diseases — such as malaria, yellow fever, dengue and Zika virus — are responsible for millions of deaths each year.

“Humans have been trying to fight mosquitoes ever since there were humans,” says Vosshall, pointing to an impressive variety of control methods — from rolled-up newspapers to genetic engineering.

“All of these advances are complementary,” says Vosshall, who argues that no single innovation can eradicate mosquito-borne diseases and advocates using several methods at once. “Our behavior control is something else in this portfolio,” she says.

This strategy seeks to reduce mosquito numbers rather than annihilate the insects entirely, which could have unintended ecological consequences. “I do worry about the balance of nature,” Vosshall says.

But not everyone agrees that eradicating mosquitoes is a bad idea. “A recent study suggested that malaria mosquitoes do not play a vital role in the ecosystem, and therefore their removal would have minimal impact,” Logan says.

“I don’t think we will ever eradicate all mosquitoes. But I do think that one day we will eradicate individual species,” he says.

It’s early days for this novel approach to mosquito control, and it remains unclear how substantially it would stem the spread of disease in the real world. Meanwhile, more lab research must be done to develop these drugs so that they are potent and cheap enough to use in the field.

“Transitioning from laboratory experiments to the field is always difficult,” Logan says. “One of the biggest challenges will be devising a system that attracts mosquitoes well enough and allows them to feed on this substance effectively.”

“You need to have dispensers; you need some way to attract female mosquitoes and have that work in local communities,” says Vosshall, looking to the logistical hurdles ahead.

Putting billions of mosquitoes on an unwitting diet was never going to be easy.

Thomas Lewton is a freelance science journalist and videographer who divides his time between London and Kampala, Uganda. You can follow him on Twitter: @thomaslewton.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))